1. Introduction

1.1. The Growing Importance of Data Analytics in Healthcare

Data analytics has become increasingly vital in healthcare, offering invaluable insights for informed decision-making. Healthcare data, whether derived from routine clinical records or gathered through specialized studies, is the cornerstone of this analysis. The meticulousness with which data variables are handled in quantitative research significantly impacts the reliability of findings. This article explores the concept of a minimum dataset for healthcare variables and, crucially, the Data Collection Tools In Health Care that are essential for acquiring this robust data.

In healthcare, data-driven decisions are far more advantageous than those based on mere observations or assumptions. However, biases in data collection and quantitative analysis must be carefully managed to ensure the validity of results, which directly influence clinical practices and patient outcomes.

The research landscape is becoming increasingly competitive, demanding rigorous scientific evaluation. While academic scrutiny exists through funding bodies, ethics committees, and peer review, the proliferation of publishing platforms, including pre-print servers accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic [1], underscores the need for high-quality, independently validated research. The quality of data underpinning healthcare research is paramount and should be a central focus of independent review processes. Even more critical is the data collection process itself, often overlooked yet potentially more influential than the data or the analysis. High-quality data collection is fundamental to trustworthy results; conversely, poor data entry leads to unreliable outputs – the “garbage in–garbage out” principle [2]. This issue can compromise individual studies and contaminate meta-analyses, which aggregate data from multiple sources [3].

This article aims to present the concept of a minimum dataset for healthcare variables and to explore the crucial data collection tools in health care that facilitate the capture of this dataset for robust study design and quantitative research appraisal.

1.2. Routine Data Sources in Healthcare: Advantages and Limitations

Healthcare settings generate vast amounts of routine data, derived from daily clinical practice and specific evaluations. When leveraging this routinely collected data for research, understanding its original purpose is crucial. This data often serves administrative functions, such as billing for healthcare services in both private and public healthcare systems. It also functions as a medicolegal clinical record, documenting diagnoses and patient management for accountability and continuity of care. However, the comprehensiveness and completeness of routinely collected data can be inconsistent. There is no guarantee that all data relevant to a specific research question is present or accurately recorded. Routine data is often evaluated through service evaluations or clinical audits to ensure adherence to standards and expected practices.

1.3. Clinical Research and Purpose-Driven Data Collection

Clinical research, where data is actively collected to answer specific research questions, generally yields superior data quality. Observational studies, in contrast, often suffer from data not collected for pre-specified purposes, lack of blinding, and inadequate control for confounding variables [4]. The reliability of observational studies is highly variable and depends on the design of databases, analysis methods, and the quality of recorded data [5]. Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) represent the gold standard in evidence-based research [6]. Active data collection in RCTs ensures the collation of data directly relevant to the research question. Data is collected to compare baseline characteristics between treatment groups, increasing the likelihood that observed effects are genuinely due to treatment differences. While RCTs are invaluable, some research questions, such as those concerning disease incidence, prevalence, and real-world clinical practice outcomes, are better addressed through other methodologies.

Consider a study investigating atrial fibrillation (AF) patients identified in primary care. Researchers might aim to study AF or evaluate clinical care and outcomes in this population. Electronic health records (EHRs) in general practices offer a seemingly straightforward way to identify AF patients through diagnosis codes. However, this approach only captures clinically recognized AF cases, missing asymptomatic individuals or those without electrocardiographic testing. To capture silent AF cases, widespread electrocardiogram screening would be necessary. This level of comprehensive data collection is crucial for prevalence studies but less critical for treatment-focused RCTs where capturing every single case might be less essential than detailed characterization of enrolled participants.

1.4. The Challenges of Data Collection in Clinical Research

New data collection for clinical research is often expensive and time-consuming. Prospective data collection requires approvals from institutional review boards, governing bodies, and ethics committees. Furthermore, research projects incur significant costs, including staff salaries, data storage, participant compensation, and institutional operating expenses, often requiring competitive research grants. These factors can create substantial barriers to data collection as protocols must be developed, reviewed, revised, approved, and verified for adherence to research guidelines. While high-quality, novel data is essential for addressing certain research questions and deriving meaningful results, it can be a resource-intensive undertaking. To improve the quality of observational data, various quality control procedures and guidelines for data acquisition, quality, and curation have been developed across healthcare settings [7,8,9].

1.5. A Collaborative Model for Enhanced Data Collection

The typical research model involves academics securing funding and navigating regulatory processes, overseeing project execution and scientific integrity. However, data collection itself is often delegated to dedicated research personnel who follow protocols, while other team members handle analysis and result presentation.

Effective data collection in research prioritizes accuracy and minimizes bias. Critical thinking about the collected data and its handling is paramount. Data collection should be evidence-based, not driven by opinions or anecdotes. Key questions arise:

- Who defines what data is collected?

- Does the research team possess adequate knowledge of the condition under study? A strong understanding of pathophysiology is crucial to avoid omitting important variables. Standardization is vital to mitigate bias related to individual familiarity.

- Does the study designer understand real-world clinical practice for the condition? For instance, in cardiology, initial contact with a cardiologist isn’t the sole point of care; general practitioners, community health professionals, paramedics, and emergency department physicians are often involved. Researchers must consider care variations across settings (rural vs. urban).

- Is the researcher familiar with prior research in the field? Systematic reviews are essential to understand existing research, ensuring new studies meet or exceed methodological standards and address identified limitations.

- Is the data to be collected reliable? Data should be accurate and internally valid, ideally also possessing external validity for generalizability.

- Does the data collector understand analytical requirements? Data collectors should understand the analytical approaches to ensure data is recorded with appropriate granularity. For example, a hypertension outcome study may require mean blood pressure, while hypertension as a covariate might only need a “yes/no” classification.

Researchers often rely on literature reviews to inform data collection methods, aiming for alignment with existing research. However, perpetuating methodological flaws from prior studies is a risk. Methods effective in one setting may not translate to others. Expert-defined data collection, based on personal experience and literature, might overlook factors outside their immediate specialty or setting, such as emergency department care or patient-specific factors like medication adherence or patient preferences. When unexpected results occur, critical assessment of data collection methods, rather than data dismissal, is crucial to understand discrepancies.

To enhance data collection quality, the “minimum dataset” framework is proposed. However, before delving into this framework, it’s important to consider the practical tools used to collect this data in healthcare.

2. Data Collection Tools in Healthcare

The effectiveness of the minimum dataset framework hinges on the availability and proper utilization of appropriate data collection tools in health care. These tools are the mechanisms through which healthcare professionals and researchers gather, store, and manage patient information. Here, we explore some essential tools:

2.1. Electronic Health Records (EHRs)

EHRs are digital versions of patients’ paper charts. They are arguably the most ubiquitous data collection tool in health care, serving as central repositories for patient demographics, medical history, diagnoses, medications, allergies, immunization status, lab results, and radiology images.

Strengths:

- Comprehensive Data Capture: EHRs are designed to capture a wide spectrum of patient data from various clinical encounters.

- Improved Accessibility and Efficiency: EHRs make patient data readily accessible to authorized healthcare providers, enhancing care coordination and reducing redundancy.

- Data Standardization: Modern EHRs often incorporate standardized terminologies (e.g., SNOMED CT, LOINC) which facilitates data aggregation and analysis.

- Integration with other Systems: EHRs can be integrated with laboratory information systems (LIS), radiology information systems (RIS), and pharmacy systems, streamlining data flow.

- Support for Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS): EHR data can power CDSS, providing alerts, reminders, and evidence-based recommendations to clinicians at the point of care.

Limitations:

- Data Quality Concerns: Data entry errors, inconsistencies in documentation practices, and incomplete records can affect data quality.

- Interoperability Challenges: While standardization efforts exist, seamless data exchange between different EHR systems remains a hurdle.

- Usability Issues: Poorly designed EHR interfaces can lead to clinician frustration and inefficient data entry.

- Cost of Implementation and Maintenance: Implementing and maintaining EHR systems can be expensive, particularly for smaller healthcare organizations.

- Privacy and Security Risks: EHRs contain sensitive patient information, making them targets for cyberattacks and requiring robust security measures.

Despite these limitations, EHRs are fundamental data collection tools in health care, providing a rich source of data for clinical care, research, and quality improvement initiatives.

2.2. Patient Registries

Patient registries are organized systems that collect uniform observational data for a population defined by a particular characteristic, such as a disease, condition, or exposure. They are powerful data collection tools in health care for tracking disease trends, evaluating treatment effectiveness, and supporting public health initiatives.

Types of Patient Registries:

- Disease Registries: Focus on patients with specific conditions (e.g., cancer registries, diabetes registries).

- Product Registries: Track the safety and effectiveness of medical devices or pharmaceutical products.

- Exposure Registries: Monitor populations exposed to specific substances or environmental factors.

- Healthcare Service Registries: Evaluate the quality and outcomes of specific healthcare services (e.g., joint replacement registries).

Strengths:

- Population-Level Data: Registries provide data on large patient populations, enabling the study of rare diseases and long-term outcomes.

- Standardized Data Collection: Registries utilize standardized data collection protocols and data dictionaries, ensuring data uniformity and comparability across sites.

- Support for Research and Quality Improvement: Registry data can be used for epidemiological research, clinical trials, quality improvement initiatives, and comparative effectiveness research.

- Benchmarking and Performance Measurement: Registries can facilitate benchmarking of healthcare providers and institutions against national or regional standards.

Limitations:

- Data Completeness and Accuracy: Registry data quality depends on the completeness and accuracy of data submitted by participating sites.

- Data Entry Burden: Data entry for registries can be time-consuming and resource-intensive for healthcare providers.

- Limited Scope: Registries typically focus on a specific condition or outcome, potentially limiting the breadth of data collected.

- Privacy and Confidentiality Concerns: Registries handle sensitive patient data and must adhere to strict privacy regulations.

Patient registries are invaluable data collection tools in health care for population health management, research, and quality of care improvement.

2.3. Wearable Devices and Mobile Health (mHealth) Technologies

The proliferation of wearable devices (e.g., smartwatches, fitness trackers) and mobile health applications (mHealth apps) has introduced a new paradigm in data collection tools in health care. These technologies enable continuous, real-time monitoring of physiological parameters and patient-reported outcomes outside of traditional clinical settings.

Types of Data Collected by Wearables and mHealth Apps:

- Physiological Data: Heart rate, activity levels, sleep patterns, blood glucose (continuous glucose monitors), blood pressure, electrocardiograms (ECGs).

- Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs): Symptoms, medication adherence, pain levels, quality of life, mood.

- Environmental Data: Location, air quality, noise levels.

Strengths:

- Continuous and Real-Time Data: Wearables and mHealth apps capture data continuously in real-world settings, providing a more holistic view of patient health.

- Patient Empowerment and Engagement: These tools empower patients to actively participate in their health management and provide valuable feedback to healthcare providers.

- Remote Monitoring and Telehealth: Wearable data facilitates remote patient monitoring, enabling timely interventions and reducing the need for in-person visits.

- Personalized Healthcare: Data from wearables can be used to personalize treatment plans and tailor interventions to individual patient needs.

Limitations:

- Data Validity and Reliability: The accuracy and reliability of data from consumer-grade wearables can vary.

- Data Overload and Integration Challenges: The sheer volume of data generated by wearables can be overwhelming, and integrating this data into EHR systems poses challenges.

- Privacy and Security Concerns: Wearable devices collect highly personal health data, raising significant privacy and security concerns.

- Digital Divide and Equity: Access to and adoption of wearable technologies may be unevenly distributed across different socioeconomic groups.

Wearables and mHealth technologies are transforming data collection tools in health care, offering unprecedented opportunities for continuous patient monitoring, personalized medicine, and proactive healthcare management.

2.4. Surveys and Questionnaires

Surveys and questionnaires remain essential data collection tools in health care, particularly for capturing patient-reported outcomes, health behaviors, and patient satisfaction. They can be administered in various formats: paper-based, electronic (online surveys), or via telephone.

Types of Surveys:

- Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs): Assess patients’ perspectives on their health status, symptoms, functional status, and quality of life.

- Health Behavior Surveys: Collect data on lifestyle factors such as diet, exercise, smoking, and alcohol consumption.

- Patient Satisfaction Surveys: Measure patients’ experiences with healthcare services and identify areas for improvement.

- Epidemiological Surveys: Gather data on disease prevalence, risk factors, and health trends in populations.

Strengths:

- Direct Patient Input: Surveys directly capture patients’ perspectives and experiences, which are crucial for holistic healthcare assessment.

- Cost-Effective and Scalable: Surveys can be relatively inexpensive to administer and can reach large populations.

- Flexibility in Data Collection: Surveys can be tailored to collect specific types of information relevant to research or clinical needs.

- Standardized Instruments: Validated and standardized questionnaires ensure data reliability and comparability.

Limitations:

- Recall Bias: Respondents may have difficulty accurately recalling past events or behaviors.

- Social Desirability Bias: Respondents may provide answers they believe are socially acceptable rather than truthful responses.

- Response Bias: Individuals who choose to participate in surveys may differ systematically from non-respondents.

- Language and Cultural Barriers: Surveys need to be culturally adapted and translated appropriately to ensure accurate data collection across diverse populations.

Surveys and questionnaires are indispensable data collection tools in health care for gathering patient-centered data and understanding various aspects of health and healthcare delivery.

2.5. Biosensors and Medical Devices

Beyond wearables, a wide array of biosensors and medical devices serve as specialized data collection tools in health care. These devices are designed to measure specific physiological parameters with high accuracy and are often used in clinical settings and for remote patient monitoring.

Examples of Biosensors and Medical Devices:

- Continuous Glucose Monitors (CGMs): Provide real-time glucose readings for diabetes management.

- Implantable Cardiac Monitors: Continuously monitor heart rhythm for arrhythmia detection.

- Remote Patient Monitoring (RPM) Devices: Transmit vital signs (e.g., blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen saturation) from patients’ homes to healthcare providers.

- Diagnostic Imaging Equipment (MRI, CT, Ultrasound): Generate detailed images of internal organs and tissues for diagnosis and monitoring.

- Laboratory Diagnostic Equipment: Analyze blood, urine, and other bodily fluids to provide objective measures of health status.

Strengths:

- High Accuracy and Precision: Medical-grade devices provide highly accurate and precise measurements of physiological parameters.

- Objective Data: Data from biosensors and medical devices is generally objective and less susceptible to subjective biases.

- Real-Time Monitoring and Early Detection: Continuous monitoring devices enable early detection of physiological changes and timely interventions.

- Improved Diagnostic Capabilities: Advanced imaging and laboratory equipment enhance diagnostic accuracy and facilitate personalized treatment.

Limitations:

- Cost and Accessibility: Medical devices can be expensive and may not be readily accessible in all healthcare settings.

- Invasiveness: Some biosensors and medical devices are invasive, requiring implantation or direct contact with the body.

- Technical Complexity: Operating and maintaining sophisticated medical devices requires specialized training and expertise.

- Data Integration Challenges: Integrating data from diverse medical devices into EHR systems can be complex.

Biosensors and medical devices are critical data collection tools in health care for accurate physiological measurement, diagnosis, and patient monitoring, particularly for managing chronic conditions and acute illnesses.

3. The Minimum Dataset Framework and Data Collection Tools

The “minimum dataset” framework, as introduced in the original article, emphasizes the need for comprehensive data collection beyond just basic variable values. It advocates for considering:

- Basic Variable Description: The fundamental value of a variable (e.g., age, smoking status). Tools like EHRs are crucial for capturing this basic information systematically.

- Severity: Indicators of the intensity or stage of a condition (e.g., NYHA heart failure classification). Tools like standardized assessment scales integrated into EHRs, PROMs collected through surveys, and objective measures from biosensors can quantify severity.

- Duration: The length of time a variable value has been present (e.g., duration of atrial fibrillation). EHRs with robust temporal data tracking, patient history modules, and even wearable devices capturing onset and duration of symptoms contribute to understanding duration.

- Time Course: How a variable changes over time (e.g., progression of diabetes). Longitudinal data within EHRs, repeated PROMs assessments via surveys, and continuous data streams from wearables provide insights into the time course of conditions.

- Validity: The accuracy and reliability of the measured variable. Data validation rules within EHRs, standardized data collection protocols in registries, and calibration procedures for medical devices are essential tools to ensure data validity.

- Modifiers: Factors that influence the impact of a variable (e.g., treatment for skin cancer). EHRs should capture treatment history, co-morbidities, and other contextual modifiers. Registries can also be designed to collect data on specific modifiers relevant to a condition.

By considering these elements of the minimum dataset, and leveraging the appropriate data collection tools in health care, researchers and clinicians can obtain richer, more meaningful data for improved healthcare insights.

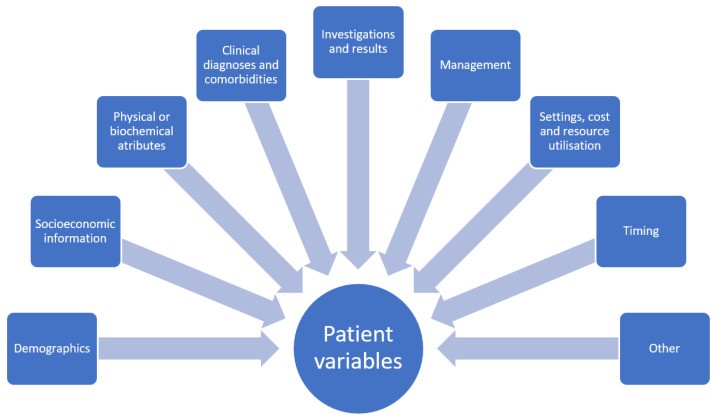

Figure 1.

Broad categories of dataset variables in healthcare, effectively captured by tools like EHRs and registries.

Figure 2.

Minimum dataset components for a single healthcare variable, highlighting the depth of information needed beyond basic values and the role of specialized data collection tools.

Figure 3.

Temporal trajectories of variables over time, illustrating the importance of time-series data captured by tools like EHRs and wearables for understanding disease progression.

4. Discussion and Implications

This exploration of data collection tools in health care and the minimum dataset framework underscores a critical shift in healthcare research and practice. The focus is moving beyond simply collecting data to ensuring the collection of meaningful and comprehensive data. While not every variable requires in-depth consideration of all minimum dataset elements, this framework provides a valuable guide when more detailed and nuanced results are desired.

Contemporary research often prioritizes study findings and their immediate impact on practice, sometimes overlooking the crucial aspect of data collection quality. There’s an assumption that proposed data collection methods are inherently satisfactory. This article encourages researchers and reviewers to critically evaluate the variables within datasets and the tools used to collect them.

Quantitative observational research inherently involves describing collected variables. However, the depth and detail of data collected for each variable are not always adequately considered. The minimum dataset concept prompts researchers to thoughtfully design study methodologies, considering whether to collect more granular data for each variable using appropriate data collection tools in health care. Similarly, peer reviewers should assess if presented variables possess sufficient detail relevant to the research question.

The “hardness” or “softness” of a variable also impacts data collection and interpretation. “Hard” variables, like mortality or age, are generally unequivocal, while “soft” variables, such as clinical signs, involve interpretation and potential subjectivity. Standardized data collection tools and protocols can help improve the reliability of both hard and soft variables. For instance, standardized scales and training can enhance the consistency of clinical sign elicitation, while calibrated equipment and automated data capture minimize errors in hard variable measurement.

Patient-reported outcomes are increasingly recognized as crucial endpoints in research, highlighting the importance of patient-centered data collection tools like PROMs surveys. Discrepancies between physician and patient perspectives underscore the need to incorporate diverse data sources for a holistic understanding of health outcomes.

Transparency in methodology is paramount for study reproducibility. Detailed descriptions of data collection tools and methods should be readily available, ideally through supplementary materials or institutional websites, even if publication word limits exist. Understanding the context of data collection, including healthcare system factors and data recording practices, is vital for accurate interpretation.

The minimum dataset framework offers a valuable tool for protocol review, study planning, and manuscript peer review. Appraising protocols and manuscripts through this lens encourages systematic consideration of whether each variable requires more detailed data collection, guided by the framework’s elements and the selection of appropriate data collection tools in health care. This is particularly relevant when study findings contradict expectations, suggesting a need for deeper variable understanding.

Despite the framework’s benefits, some questions remain regarding optimal data collection depth. While literature reviews and expert consultation are helpful, subjective judgments by researchers are still necessary to determine the appropriate level of data granularity. The ideal amount of data to collect is question-specific, aiming for a balance between comprehensiveness and analytic manageability.

Limitations of the minimum dataset approach include potential complexity and increased time for data collection and analysis. Some may argue that basic variable collection suffices, but this assumption should be rigorously justified, proving that duration, severity, and time course are indeed irrelevant to the research question. Furthermore, applying the minimum dataset to pre-existing routine data may be constrained by the data already collected.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the minimum dataset framework offers a valuable paradigm shift in how we approach data collection in healthcare. By prompting a more comprehensive consideration of variables beyond basic descriptors, and by emphasizing the strategic selection and utilization of data collection tools in health care, this framework has the potential to significantly enhance data quality and improve our understanding of complex healthcare phenomena. Future research should focus on empirically evaluating the impact of this framework on data collection practices and the quality of resulting datasets and research outcomes. The strategic and thoughtful application of appropriate data collection tools in health care, guided by frameworks like the minimum dataset, is paramount to advancing healthcare knowledge and improving patient care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S.K.; methodology: C.S.K., E.-A.M., C.D.M. and J.A.B.; resources: C.S.K., E.-A.M., C.D.M. and J.A.B.; writing-original draft preparation: C.S.K.; writing-review and editing: C.S.K., E.-A.M., C.D.M. and J.A.B.; visualization: C.S.K., E.-A.M., C.D.M. and J.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was not required for this theoretical manuscript. No patient data was utilized for the manuscript, so patient consent was not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. C.D.M. received funds from Bristol Myer Squibb for academic support for a non-pharmacological atrial fibrillation screening trial but this is not related to this work. C.D.M. is also funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration West Midlands, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research Professorship.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[1] Fraser, N.; Brierley, J.; Dey, G.; Polka, J.K.; Pálfy, M.; Nanni, F.; Collings, R.; Jessop, Z.C.; Nielsen, L.R.; Hamilton-Jewell, R.; et al. The evolving role of preprints in the dissemination of COVID-19 research and their impact on the science–policy interface. Clin. Pract. 2022, 12, 295–320.

[2] van de Water, A. Garbage in–garbage out. Clin. Pract. 2022, 12, 321–322.

[3] Ioannidis, J.P.A. Meta-research: Evaluating and improving research practices. PLoS Biol. 2005, 3, e37.

[4] Rothman, K.J.; Greenland, S.; Lash, T.L. Modern Epidemiology, 3rd ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008.

[5] Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1500–1524.

[6] Burns, P.B.; Rohrich, R.J.; Chung, K.C. The levels of evidence and their role in evidence-based medicine. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 128, 305–310.

[7] Kahn, M.G.; Callahan, T.J.; Barnard, J.; Brown, J.S.; Davidson, P.; Dowling, J.N.;ዱርham, W.E.; Evans, J.P.; Fuller, S.; Goldberg, H.S.; et al. Data quality assessment: Report from the PCORnet Data Quality Task Force. eGEMs Gener. Evid. Methods Improve Patient Outcomes 2016, 4, 1241.

[8] Weiskopf, N.G.; Weng, C.; Lai, A.M.; Ramirez, R.L.; Starren, J.B.; Payne, P.R.;ুণs, J.C. Recommendations for improving the quality of EHR data used for clinical research: A Delphi study. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2013, 20, 962–970.

[9] Chapman, W.W.; Dowling, J.N.; Knudson, J.D.;砂eberg, D.E.; Kahn, M.G. Evaluation of the rapidly applied data quality assessment (RAD-QA) tool. Inform. J. Health Soc. Care 2017, 42, 115–124.

[10] Nomenclature and Criteria for Diagnosis of Diseases of the Heart and Great Vessels. 9th ed. Boston: Little, Brown & Co; 1994.

[11] Yancy, C.W.; Jessup, M.; Bozkurt, B.; Butler, J.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Drazner, M.H.; Fonarow, G.C.; Geraci, A.U.; Horwich, T.; Januzzi, J.L.; et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, e147–e239.

[12] Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Anker, S.D.; Bueno, H.; Cleland, J.G.V.; Coats, A.J.S.;ૂrger, W.; Danchin, N.; Filippatos, G.; Gonzalez-Juanatey, J.R.; et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 2129–2200.

[13] Trochim, W.M.K. Research Methods Knowledge Base; Atomic Dog Publishing: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2006.

[14] Ndrepepa, G. Contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary interventions and cardiac surgery: Incidence, risk factors, prognosis, and prevention. Clev. Clin. J. Med. 2011, 78, 77–87.

[15] Mahmood, S.S.; Mahmood, F.; Rehman, S.; Khan, S.U.; Chen, P.C.; Riaz, H.; Khoueiry, G.;ুল, S.;ুল, S.; Steigner, Z.; et al. Myocarditis and pericarditis after mRNA COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2021, 7, 751–759.

[16] Lysen, H.K. Anthropometric measurements. In Clinical Assessment of Nutritional Status; Lee, R.D., Nieman, D.C., Eds.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 279–332.

[17] Weber, M.A.; Julius, S. Surrogate endpoints in hypertension trials. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2000, 14, 487–490.

[18] Lesko, L.J.; Atkinson, A.J., Jr. Use of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in drug development and regulatory decision making: Criteria, validation, strategies. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001, 41, 347–366.

[19] Basch, E.; Abernethy, A.P. Moving quality beyond the clinic. JAMA 2011, 305, 2531–2532.

[20] Yusuf, S.; Hawken, S.; Ounpuu, S.; Dans, T.; Avezum, A.; Lanas, F.; McQueen, M.; Budaj, A.;ூn, P.; Lisheng, L.; et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet 2004, 364, 937–952.

[21] Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010, 340, c332.

[22] von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457.