Abstract

Background

Assessing pain in brain-injured patients within the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) poses significant challenges. Existing pain scales may not accurately capture the unique behavioral responses of this patient population. This study aimed to validate the French-Canadian and English revised versions of the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool Gelinas (CPOT-Neuro) specifically for brain-injured ICU patients.

Methods

A prospective cohort study was conducted across four sites – three Canadian and one American. Patients with traumatic or non-traumatic brain injuries were evaluated using the CPOT-Neuro by trained assessors (research staff and ICU nurses). Assessments were performed before, during, and after both nociceptive procedures (turning, etc.) and non-nociceptive procedures (non-invasive blood pressure, soft touch). Conscious and delirium-free patients were asked to self-report their pain intensity on a scale of 0–10. An initial dataset was collected for all participants (n = 226), followed by a second dataset (n = 87) when a change in the Level of Consciousness (LOC) was observed post-enrollment. Patients were categorized into three LOC groups: (a) unconscious (Glasgow Coma Scale or GCS 4–8); (b) altered LOC (GCS 9–12); and (c) conscious (GCS 13–15).

Results

CPOT-Neuro scores were significantly higher during nociceptive procedures compared to periods of rest and non-nociceptive procedures in both datasets (p < 0.001). CPOT-Neuro cutoff scores of ≥ 2 and ≥ 3 effectively identified mild to severe self-reported pain ≥ 1 and moderate to severe self-reported pain ≥ 5, respectively. Interrater reliability of CPOT-Neuro scores among raters was strong, with intraclass correlation coefficients > 0.69.

Conclusions

The Critical Care Pain Observation Tool Gelinas (CPOT-Neuro) demonstrated validity in this multi-center study involving brain-injured ICU patients across varying LOC. Further implementation studies are crucial to assess the tool’s effectiveness in routine clinical practice.

Supplementary Information

The online version includes supplementary material accessible at 10.1186/s13054-021-03561-1.

Keywords: Validation, Pain, Assessment, Brain Injury, Critical Care, Critical Care Pain Observation Tool Gelinas

Background

The Society of Critical-Care Medicine (SCCM) guidelines from 2013 highlighted the critical need for validating behavioral pain scales for brain-injured patients in the ICU [1]. Since then, research has focused on evaluating the two recommended scales: the Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS [2]) and the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool (CPOT [3]) for pain assessment in this specific patient group. Studies have explored the BPS (six studies [4–9]) and the CPOT (six studies [10–15]), with one study utilizing both [16] in brain-injured ICU patients. These studies, encompassing 193 patients for BPS and 690 for CPOT validations, with over half being mechanically ventilated, consistently reported elevated behavioral scores during nociceptive procedures (e.g., turning, endotracheal suctioning) compared to rest or non-nociceptive procedures (e.g., eye care, non-invasive blood pressure [NIBP] with cuff inflation or soft touch).

Despite the demonstrated ability of both BPS and CPOT to differentiate between nociceptive and non-nociceptive stimuli, item-level issues have emerged. For instance, the facial expression item of the BPS showed a smaller effect size for responsiveness between rest and nociceptive procedures compared to the upper limbs item [9]. Similarly, grimacing and muscle rigidity, as assessed by the original CPOT [11], were infrequently observed in brain-injured ICU patients. However, grimacing was identified as a strong predictor of self-reported pain intensity in conscious and reliably communicative (non-delirious) brain-injured ICU patients [17]. Additional pain behaviors not included in the original scales, such as orbit tightening, eye weeping (tearing), and face flushing, have been documented in this specific patient group [17–19]. Low Levels of Consciousness (LOC) or deep sedation, common in brain-injured ICU patients, were associated with reduced frequencies of pain-indicative behaviors [17–19] and lower behavioral scale scores [8, 9, 12, 20]. Adapting existing pain scales to better suit brain-injured ICU patients could enhance their applicability and accuracy in pain detection within this vulnerable population. While tools like the Nociception Coma Scale [21] and its revised version [22] are available for brain-injured patients with disorders of consciousness, they are not designed for the ICU setting and are unsuitable for mechanically ventilated patients [23].

This study aimed to validate the French-Canadian and English revised versions of the CPOT for brain-injured ICU patients, known as the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool Gelinas (CPOT-Neuro). The specific objectives were to evaluate:

- Criterion Validation: The association between CPOT-Neuro scores and patient self-reporting (the gold standard for pain measurement), and the CPOT-Neuro’s ability to detect self-reported pain in brain-injured ICU patients.

- Discriminative Validation: The capacity of CPOT-Neuro scores to distinguish between non-nociceptive and nociceptive procedures, and, where feasible, changes in scores before and after opioid administration.

- Interrater Reliability: The level of agreement in CPOT-Neuro scores between trained research staff and ICU nurses.

Methods

Design

This multicenter validation study employed a prospective cohort design with repeated measures. This approach facilitated the assessment of reliability and validity for both French-Canadian and English versions of the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool Gelinas (CPOT-Neuro), using data collected across multiple procedures and time points.

Settings

The study was conducted in four neurotraumatology ICUs across Canada (two in Montreal, Quebec; one in Toronto, Ontario) and the USA (one in Seattle, Washington). The settings included a French-speaking site (Montreal, Canada), a bilingual site (Montreal, Canada), and two English-speaking sites (Toronto, Canada and USA). All participating ICUs had similar capacities (22–30 beds) and annual patient admissions (1000–1500). Pain management protocols were individualized across all sites.

Sample

The study aimed for a heterogeneous population of brain-injured ICU patients to ensure the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool Gelinas (CPOT-Neuro) validation was generalizable to a broad brain-injured population, rather than specific diagnostic groups. Inclusion criteria were: (1) age 18 years or older; (2) ICU admission for brain injury less than 4 weeks (e.g., traumatic brain injury [TBI] with or without other trauma, ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke including cerebral aneurysm, cerebral tumor, or brain injury from other causes); and (3) a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS [24]) score ≥ 4. Exclusion criteria, designed to minimize confounding variables and ensure observable behavioral reactions, included: (1) spinal cord injury affecting motor activity in all four limbs; (2) pre-existing cognitive deficits or psychiatric conditions (e.g., psychosis, suicidal ideation); (3) prior diagnosis of epilepsy; (4) use of neuromuscular blocking agents; (5) Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS [25]) score of − 5 (unarousable); and (6) suspected brain death. In compliance with regulations in Quebec and Ontario, informed written consent was obtained from participants (patients or their representatives for incapacitated patients) in the Canadian ICUs. As an observational, non-interventional study, informed written consent was not required in Washington State. Recruitment and data collection spanned from June 2015 to December 2016.

Procedures

Data collection occurred before and during non-nociceptive (NIBP, soft touch) and nociceptive (turning and others detailed in Table 1) procedures, as well as before and after opioid administration. NIBP, involving cuff inflation (standard bedside equipment), was used as a non-nociceptive procedure, consistent with findings that it is painless for ICU patients, including those with brain injuries [10, 15, 26]. NIBP and all nociceptive procedures were part of routine ICU care. Soft touch, a research-added non-nociceptive procedure, involved research staff, ICU nurses, or family members gently touching the patient’s forearm for one minute [27], also found to be painless in brain-injured ICU patients [11, 13]. These procedures were selected to assess the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool Gelinas (CPOT-Neuro)’s ability to discriminate between procedures likely to be painful versus painless (discriminative validation). Each patient underwent six to ten assessment time points per dataset (three to five procedures per patient, with two assessment points per procedure). All patients had at least one dataset upon study enrollment, and some had a second if their LOC changed during their ICU stay after enrollment. LOC was classified based on Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores: unconscious (GCS ≤ 8), altered LOC (GCS 9–12), and conscious (GCS 13–15) [24].

Table 1. Frequency of nociceptive procedures observed in the ICU

| Nociceptive procedures | 1st data set Frequency (n) | 2nd data setb Frequency (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Turning | 211 | 81 |

| Endotracheal suctioning | 29 | 7 |

| Mouth suctioning/care | 16 | 5 |

| Repositioning | 14 | 1 |

| Mobilization/physiotherapy | 9 | 1 |

| Parenteral injection/IV insertion | 9 | 8 |

| Blood draw | 8 | 0 |

| Dressing change | 7 | 3 |

| Finger prick | 5 | 0 |

| Arterial/central line removal | 4 | 0 |

| Drain removal | 3 | 1 |

| Nasogastric tube/Dobhoff insertion | 3 | 0 |

| Endotracheal tube removal | 2 | 0 |

| Other common ICU proceduresa | 9 | 1 |

| Total | 329 | 108 |

aExamples: Codman catheter insertion, manipulation of affected limb, collar care

bA second data collection was conducted with participants who experienced a change in their level of consciousness during their participation in this study

Pain assessment using the Critical Care Pain Observation Tool Gelinas (CPOT-Neuro) was conducted by trained research staff. For turning and other nociceptive procedures, whenever possible, a trained ICU nurse was also asked to independently complete the CPOT-Neuro to assess interrater reliability. Patients were assessed for one-minute periods or the duration of the nociceptive procedure. Raters scored each CPOT-Neuro item. Following the CPOT-Neuro assessment, research staff asked conscious and non-delirious patients to verbally (yes/no) or nonverbally (e.g., head nodding) report pain presence/absence and then rate pain intensity using the 0–10 Faces Pain Thermometer (FPT) visual format [28]. Patient self-report served as the reference standard for pain measurement, used to establish criterion validation of the CPOT-Neuro.

Instruments

CPOT-Neuro

The CPOT-Neuro is an adapted version of the original CPOT. The original tool [3] comprises five behavioral items: (a) facial expression, (b) body movements, (c) compliance with ventilator (for mechanically ventilated patients) or (d) vocalization (for non-intubated patients), and (e) muscle tension. Each item is scored 0–2, resulting in a total score range of 0–8. Higher scores indicate more intense behavioral reactions, with a cutoff score ≥ 2 suggesting the presence of pain [10, 11, 23, 29].

The adaptation process involved reviewing each item and score of the original CPOT in light of observational data on pain-related behaviors in brain-injured ICU patients [17, 18, 30]. Input on the relevance of these behaviors for pain assessment in this population was also gathered from 61 ICU nurses, 13 physicians, and 3 physiotherapists [31].

Modifications were implemented across all items. Scores of 0 remained unchanged for all items. For facial expression, a score of 1 was redefined to include only brow lowering, identified as a common reaction to pain in brain-injured ICU patients regardless of LOC [17, 18], and deemed relevant by ICU clinicians [31]. A score of 2 was modified to include at least two upper face contractions (e.g., brow lowering + eye tightening) or grimacing. Grimacing is the strongest predictor of pain intensity in this group [17] and highly relevant according to clinicians [31]. For body movements, scores of 1 and 2 were also revised. A score of 1 now included non-purposeful movements like cautious movements or limb flexion. A score of 2 was related to protective or purposeful movements, such as attempting to reach or touch the pain site, considered highly relevant by clinicians [31]. These body movement descriptions better reflect observations in brain-injured ICU patients [17]. In ventilator compliance, only the score of 1 description was modified to include alarm activation. Coughing was removed due to clinician feedback on irrelevance [31]. For vocalization, verbal pain complaints were added to score 2, considered relevant by clinicians for conscious or altered LOC brain-injured patients [31]. The score of 2 (very tense) for muscle tension was removed due to potential confusion with spasticity post-brain injury, as noted by clinicians [31]. Autonomic responses like tearing and face flushing, newly documented in brain-injured ICU patients [17, 19], were also rated as relevant by clinicians for conscious or altered LOC patients [31]. A score of 1 was assigned for the presence of at least one autonomic response. The CPOT-Neuro’s total score ranges from 0 to 8, consistent with the original CPOT.

The CPOT-Neuro was initially adapted into French-Canadian from the original French-Canadian CPOT version [32] and then translated into English using forward–backward translation. Both versions were validated concurrently in this study. The CPOT-Neuro description is available in Additional file 1.

Raters and CPOT-Neuro Training

Raters included 11 research staff and 36 ICU nurses. Research staff consisted of 2 nursing researchers, 2 clinical research coordinators, 6 nursing research trainees, and one medical student. ICU nurses were predominantly female (89%), with college (33%) or university degrees (66%), and ICU experience ranging from 2 to 34 years (median = 8.00 [IQR = 5.25–16.75]). In one Canadian ICU, only research staff performed CPOT-Neuro assessments. In others, both research staff and ICU nurses participated.

Training was conducted by the PI (CG), the author of CPOT/CPOT-Neuro, using a standardized session based on the original CPOT training [33]. The 45-minute session detailed each CPOT-Neuro item and scoring, using illustrations and pictures. Training was in small groups or individually. Three patient videos were used for scoring practice and discussion. Post-training, raters scored three additional videos in writing. Consistency was expected, with a total score difference no greater than one point, deemed acceptable in previous CPOT training [34]. If differences of two or more points occurred, CPOT-Neuro scoring was clarified before the next video. Over 73% of raters at each site achieved acceptable scores for all three videos, and fewer than 25% had score differences ≥ 2 for at most two videos [35]. An overall Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) of 0.85 (95% CI [0.59–1.00]) was achieved for all raters’ scores across the three videos. Further training details are published elsewhere [35].

Participant’s self-report

Following each CPOT-Neuro assessment, conscious, self-reporting, and non-delirious patients (see Screening of delirium) were asked “Do you have pain?” and to answer “yes” or “no” verbally or nonverbally. Then, they rated pain level using the 0–10 Faces Pain Thermometer (FPT) visual format. The FPT, developed and tested in critically ill adults by the PI [28], has been used in brain-injured ICU patient studies [10, 11, 17, 18, 28]. It features a thermometer graded 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain), with six faces adapted from Prkachin’s work [36]. The scale has shown good convergent (r = 0.80–0.86 with a descriptive rating scale [28]) and discriminative validation when comparing scores at rest, during nociceptive and non-nociceptive procedures [10, 11, 26, 28, 30, 37].

Socio-demographic and clinical variables

Data collected for each participant included: demographics (sex, age) and clinical data from medical charts: diagnosis, illness severity (APACHE II score [38]), neuroanatomical lesion location (diffuse, frontal, parietotemporal, occipital, subcortical), level of consciousness (GCS score or adapted version [24, 39]), sedation level (RASS score [25]), and administration of analgesic/sedative agents (IV infusions, and boluses within one hour pre-procedure).

Screening of delirium

Delirium screening was performed prior to data collection in all conscious patients able to communicate. Delirium can compromise self-report reliability [23]. Trained research staff used either the CAM-ICU [40] or ICDSC (Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist [41]), depending on ICU standard practice, to screen for delirium. CAM-ICU and ICDSC are considered the most reliable and valid delirium assessment tools for critically ill adults based on a recent systematic review [42].

Data analysis

Sample size calculation, using MedCalc and G*Power, was based on criterion validation requirements using patient self-reporting and the need to represent brain-injured ICU patients at various LOC. A minimum of 52 conscious self-reporting patients was needed for a moderate correlation of 0.50 (as found in previous CPOT validation studies [3, 10, 11, 26, 43, 44]) with 90% power and a 0.01 significance level (Bonferroni correction). For ROC curve analysis (AUC of 0.80, negative/positive case ratio 0.6 during procedural pain [11, 29]), 50 patients were required (90% power, 0.01 significance). Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test (minimum 50 patients per LOC group, effect size 0.50, 0.01 significance) would provide 85% power.

SPSS software (version 24.0) was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated for socio-demographic and clinical data. Nonparametric tests were used due to non-normal variable distribution (Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests, p > 0.05; skewness and kurtosis indices > ± 2 [45]). Kruskal-Wallis and Mann–Whitney U tests compared CPOT-Neuro scores across analgesia/sedation regimen, medical diagnosis, and sedation level groups. Criterion validation was assessed using Spearman’s rho correlation between self-reported pain intensity and CPOT-Neuro scores. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis evaluated the CPOT-Neuro’s ability to classify patients with/without pain and at different pain intensity levels (≥ 1 for any pain, ≥ 5 for moderate to severe pain), and to determine optimal cut-off scores. Discriminative validation of CPOT-Neuro scores across time points and procedures used the Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test. Interrater reliability between research staff and ICU nurses was assessed using Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) (two-way mixed model). Missing data were not imputed. Data analysis was performed by a PhD-prepared health professional uninvolved in data collection.

Results

Sample description

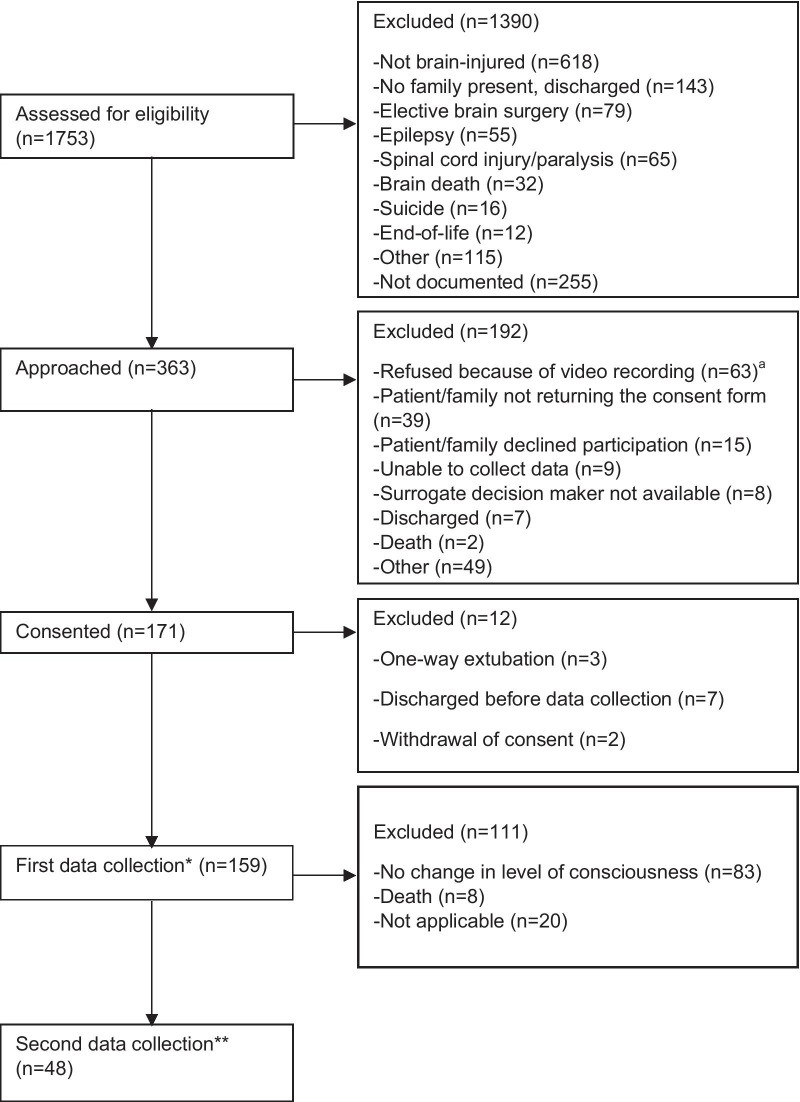

A total of 226 patients participated in the first data set, and 87 of these had a second data set collected due to LOC changes during their ICU stay (Fig. 1). In both datasets, median patient age was > 50 years, the majority were male (> 65%), White Caucasian (> 80%), and admitted post-TBI (> 55%), with frontal lobe injuries being most common (Table 2). RASS sedation levels indicated patients were generally drowsy (− 1) or sedated. Approximately half were mechanically ventilated.

Fig. 1.

Participant flow diagram—Canadian sites. aPatients were video recorded in Montreal sites only. *67 from the American site for a total of 226 participants in the first data set. **39 from the American site for a total of 87 participants in the second data set

Table 2. Socio-demographic and medical data of brain-injured ICU patients at each data set

| 1st data set (n = 226) | 2nd data set (n = 87) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Median | 58 | 53 |

| Interquartile range (IQR) | 39.5–75 | 37–67 |

| Sex: n (%) | ||

| Male | 154 (68%) | 57 (66%) |

| Female | 72 (32%) | 30 (34%) |

| Diagnosis: n (%) | ||

| Traumatic brain injury (TBI) | 134 (59%) | 48 (55%) |

| Neuro-medicala | 92 (41%) | 39 (45%) |

| Location of brain injury in | n = 93 | n = 34 |

| TBI Patients: n | ||

| Frontal | 78 | 33 |

| Parietal | 40 | 11 |

| Temporal | 46 | 15 |

| Occipital | 19 | 10 |

| Missing | 41 | 14 |

| Mechanically ventilated: n (%) | 101 (45%) | 46 (53%) |

| APACHEa score | ||

| Median | 16 | 18 |

| Range | 0–35 | 6–35 |

| Level of Consciousness: n (%) | ||

| Unconscious (GCSb 4–8) | 36 (16%) | 14 (16%) |

| Altered (GCS 9–12) | 63 (28%) | 27 (31%) |

| Conscious (GCS 13–15) | 127 (56%) | 46 (53%) |

| RASSc | ||

| Median | − 1 | − 1 |

| Range | − 4 to + 3 | − 4 to + 3 |

| Missing data n (%) | 24 | – |

| Awake (RASS = 0) | 73 (32%) | 20 (23%) |

| Sedated (RASS = − 1 to − 4) | 104 (46%) | 52 (60%) |

| Agitated (RASS = + 1 to + 3) | 25 (11%) | 15 (17%) |

| CAM-ICUd: n (%) | ||

| Negative | 74 (33%) | 18 (21%) |

| Positive | 20 (9%) | 10 (11%) |

| Not Measurable | 132 (58%) | 59 (68%) |

Injury could be located in more than one area

Neuro-medical diagnoses include ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, cerebral aneurysm and tumor, and other non-traumatic brain injury

aAPACHE: Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation

bGCS: Glasgow Coma Scale

cRASS: Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale

dCAM-ICU: Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit

Regarding analgesia and sedation in the first dataset, over half of patients received no analgesia/sedation before nociceptive procedures (turning: 54%, other procedures: 53%), while some received continuous analgesia and/or sedation (turning: 41%, other procedures: 42%). Only 5% and 4% received a bolus within one hour before turning and other procedures, respectively. Total CPOT-Neuro scores during turning and other procedures were not significantly different across analgesia/sedation regimens (Kruskal Wallis test = 0.35 and 1.91, p = 0.950 and 0.591) and medical diagnoses (TBI vs. neuro-medical; Mann–Whitney U test = 4859.00 and 1501.50, p = 0.268 and 0.914). Similar results were found in the second dataset.

Of conscious patients, 52% could communicate, but 19% screened positive for delirium and were excluded from criterion validation analyses. Criterion validation analyses included self-reports from 77 patients during turning and 30 during other nociceptive procedures. All self-reports were independent data.

Description of CPOT-Neuro scores

In the first dataset, total CPOT-Neuro scores were low (median = 0) at rest, post-opioid administration, and during non-nociceptive procedures (NIBP, soft touch) (Table 3). At these times, patients mainly showed neutral behaviors: relaxed facial expression, absence of autonomic responses and body movements, relaxed muscles, and ventilator tolerance or normal vocalization. Higher total CPOT-Neuro scores were observed pre-opioid, during turning, and other nociceptive procedures. Similar results were found in the second dataset subgroup (Table 4).

Table 3. Frequency (%) of behavioral items and descriptive statistics of CPOT-Neuro scores during the first data set

| Items | Procedures