Clinical outcomes for patients in Intensive Care Units (ICUs) can vary significantly across different hospitals and healthcare systems. While numerous factors contribute to these differences, including patient mix, ICU volume, and staffing models, ICU acuity has emerged as a critical element. ICU acuity refers to the average severity of illness of patients within a specific ICU. Interestingly, studies have shown that admission to high-acuity ICUs, those that typically manage patients with more severe conditions, is often associated with improved patient outcomes compared to low-acuity ICUs. The reasons behind this phenomenon are not entirely clear, prompting researchers to investigate the underlying mechanisms.

One compelling hypothesis is that high-acuity ICUs are more effective at implementing and standardizing evidence-based processes of care. These processes, grounded in clinical research and best practices, are crucial for enhancing patient safety and improving outcomes. They offer a tangible framework for quality improvement, allowing clinicians to target specific areas for enhancement within defined patient populations. However, the consistent adoption of these evidence-based practices across all ICUs remains a challenge. Variable adherence can signal potential gaps in care quality, potentially leading to suboptimal results for patients.

This study delves into the relationship between ICU acuity and the application of five key evidence-based care processes within ICUs participating in a large telemedicine program across the United States. The focus is on processes meticulously tracked by the Philips ICU telemedicine system, a system designed to monitor hospital performance and drive continuous quality improvement. These processes include:

- Adherence to Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis

- Adherence to Stress Ulcer prophylaxis

- Avoidance of Hypoglycemia

- Avoidance of Sustained Hyperglycemia

- Avoidance of Liberal Transfusion Practices

The central question is whether high-acuity ICUs demonstrate greater adherence to these vital evidence-based practices compared to their low-acuity counterparts. Understanding this relationship can provide valuable insights into how to elevate the quality of critical care across all ICU settings, regardless of their acuity level.

Methods

This research employed a retrospective cohort study design, utilizing data from the Philips eICU Research Institute, a vast repository encompassing clinical and administrative data from over 320 hospitals across the United States. The participating ICUs represent a diverse range of facilities, including critical access, community, and referral hospitals, serving communities of varying sizes and demographics. The Philips eICU Research Institute database provides granular, standardized data on patient admissions, discharges, demographics, laboratory results, and medication records, offering a robust platform for this type of investigation.

Study Population

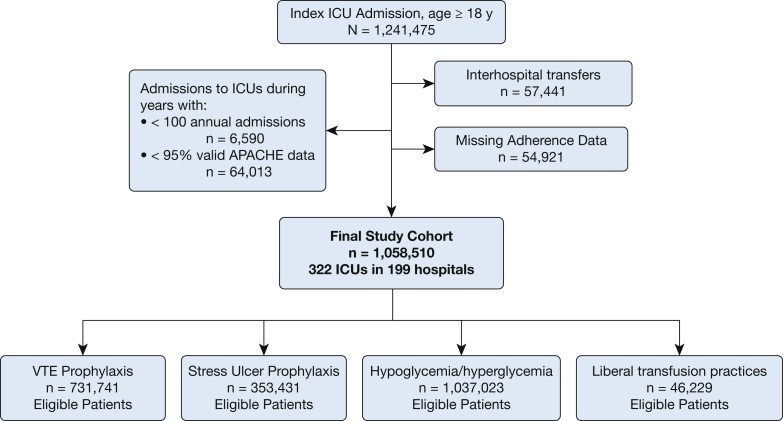

The study cohort comprised adult patients (aged 18 years and older) admitted to ICUs within the Philips ICU telemedicine program between 2010 and 2015. Patient selection criteria are detailed in Figure 1. Exclusions were applied to ensure data integrity and study validity. Patients with incomplete data necessary for calculating the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IVa score were excluded. Additionally, patients transferred from or to other facilities were removed due to incomplete hospital course information. To maintain data independence, only the initial ICU admission for patients with multiple admissions was included. Admissions to ICUs with very low annual volume (< 25 admissions per year) were also excluded to ensure a sufficient patient population for analysis within each ICU.

Figure 1.

Figure 1: Patient selection flowchart outlining inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study cohort. This chart details the process of filtering patients to ensure a robust and relevant dataset for analyzing the relationship between ICU acuity and evidence-based care.

Acuity Measurement and Outcomes

The primary exposure variable was ICU acuity, quantified as the mean APACHE IVa score of all patients admitted to an ICU within a calendar year. The APACHE IVa score is a validated tool used to assess the severity of illness in ICU patients, considering physiological variables, diagnoses, and comorbidities to predict outcomes such as mortality and length of stay. To facilitate comparison and interpretation, ICUs were categorized into quartiles based on their annual mean APACHE IVa scores: low, medium, high, and highest acuity. It’s important to note that ICUs could shift between acuity categories across different years within the study period depending on their relative mean APACHE IVa scores. Teaching hospitals were identified based on their membership in the Council of Teaching Hospitals and Health Systems.

The primary outcomes assessed were adherence to VTE and stress ulcer prophylaxis among eligible patients and the avoidance of potentially harmful events: hypoglycemia, sustained hyperglycemia, and liberal transfusion practices. These outcomes are routinely monitored by the Philips ICU telemedicine program to evaluate ICU performance and adherence to evidence-based care standards. Eligibility criteria and definitions for each outcome were rigorously defined based on established clinical guidelines and the protocols of the Philips ICU telemedicine program. For example, patients were deemed eligible for VTE prophylaxis if they were admitted to the ICU for more than 24 hours, unless they were already receiving full-dose anticoagulation or had a documented contraindication. Adherence was defined by documented administration of pharmacological or mechanical prophylaxis within 48 hours of ICU admission. Similar criteria and definitions were established for stress ulcer prophylaxis, hypoglycemia, sustained hyperglycemia, and liberal transfusion practices, ensuring consistent and objective outcome measurement.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed at the patient level, focusing on patients eligible for each specific intervention. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics and unadjusted outcomes across different ICU acuity levels. Chi-square tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to assess unadjusted differences between acuity groups, as appropriate for categorical and continuous variables respectively. Table 1 presents a summary of these descriptive statistics.

Table 1.

Characteristics and Unadjusted Outcomes of Patients Stratified According to ICU Acuity

| Variable | Low-Acuity ICUs (n = 224,294) | Medium-Acuity ICUS (n = 237,128) | High-Acuity ICUs (n = 260,372) | Highest Acuity ICUs (n = 336,716) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 62.8 ± 17.1 | 63.8 ± 16.7 | 63.4 ± 17.0 | 63.5 ± 16.9 |

| Male sex | 120,002 (53.5) | 128,884 (54.4) | 139,807 (53.7) | 180,612 (53.6) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 170,591 (76.1) | 179,034 (75.5) | 202,091 (77.6) | 251,840 (74.8) |

| Black | 24,442 (10.9) | 28,747 (12.1) | 25,948 (10.0) | 40,643 (12.1) |

| Other | 29,261 (13.0) | 29,347 (12.4) | 32,333 (12.4) | 44,233 (13.1) |

| APACHE IVa score | 47.8 ± 21.8 | 52.4 ± 22.7 | 56.1 ± 24.7 | 62.8 ± 27.8 |

| Admission source | ||||

| ED | 121,960 (54.4) | 127,231 (53.7) | 142,233 (54.6) | 183,399 (54.5) |

| Operating room | 34,083 (15.2) | 44,405 (18.7) | 40,496 (15.6) | 43,639 (13.0) |

| Ward transfer | 28,105 (12.5) | 33,127 (14.0) | 40,475 (15.5) | 57,411 (17.1) |

| Direct admission | 21,524 (9.6) | 16,110 (6.8) | 18,818 (7.2) | 26,122 (7.8) |

| Other | 18,622 (8.3) | 16,255 (6.9) | 18,350 (7.0) | 26,145 (7.8) |

| Admitting diagnosis | ||||

| Cardiac | 55,795 (24.9) | 74,383 (31.4) | 68,566 (26.3) | 74,456 (22.1) |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 4,126 (1.8) | 4,992 (2.1) | 5,689 (2.2) | 7,969 (2.4) |

| GI bleeding | 9,876 (4.4) | 12,646 (5.3) | 15,349 (5.9) | 23,062 (6.8) |

| Neurologic | 42,292 (18.9) | 24,772 (10.4) | 27,658 (10.6) | 30,777 (9.1) |

| Overdose | 6,025 (2.7) | 6,742 (2.8) | 8,004 (3.1) | 10,280 (3.1) |

| Respiratory | 5,246 (2.3) | 7,282 (3.1) | 7,473 (2.9) | 10,167 (3.0) |

| Sepsis | 34,884 (15.6) | 44,781 (18.9) | 56,180 (21.6) | 95,483 (28.4) |

| Trauma | 16,115 (7.2) | 9,174 (3.9) | 11,833 (4.5) | 12,124 (3.6) |

| Other | 49,935 (22.3) | 52,356 (22.1) | 59,620 (22.9) | 72,398 (21.5) |

| ICU LOS, d | 2.8 ± 3.5 | 2.9 ± 3.7 | 2.9 ± 3.7 | 3.2 ± 4.1 |

| ICU mortality | 8,493 (3.8) | 10,682 (4.5) | 14,287 (5.5) | 25,367 (7.5) |

| Hospital LOS, d | 6.8 ± 6.5 | 7.4 ± 7.0 | 7.7 ± 7.2 | 8.7 ± 8.2 |

| Hospital mortality | 15,640 (7.0) | 18,648 (7.9) | 22,914 (8.8) | 39,397 (11.7) |

Table 1: Baseline characteristics and unadjusted clinical outcomes for patients categorized by ICU acuity level. This table presents a comparative overview of patient demographics, severity of illness scores, admission details, diagnoses, and mortality rates across low, medium, high, and highest acuity ICUs.

Multivariable analyses were conducted using mixed-effects logistic regression models to examine the relationship between ICU acuity and the outcomes of interest, adjusting for potential confounders. ICU was included as a random effect to account for the non-independence of patients within the same ICU. Hospital discharge year was included as a fixed effect to control for temporal trends in practice patterns. A priori selected covariates included APACHE IVa score, year of hospital discharge, ICU type, ICU volume, hospital bed size, and teaching hospital status. Sensitivity analyses were performed, including defining ICU acuity as a continuous variable and restricting the cohort to low-risk patients (APACHE IVa-predicted hospital mortality ≤ 3%). Post hoc exploratory analysis tested for interaction between ICU acuity and teaching status to investigate potential organizational factors influencing adherence to evidence-based practices.

Results

The final study population comprised 1,058,510 patients admitted to 322 ICUs across 199 hospitals. Table 1 details the characteristics and unadjusted outcomes of patients stratified by ICU acuity. The most frequent admitting diagnosis was cardiac-related, and the emergency department was the most common admission source across all acuity levels. Approximately 60% of the ICUs were mixed medical-surgical units. Hospitals varied in size and patient volume, with the majority being non-teaching hospitals (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of ICUs Stratified According to ICU Acuity

| Characteristic | Low-Acuity ICUs (n = 131) | Medium-Acuity ICUs (n = 151) | High-Acuity ICUs (n = 146) | Highest Acuity ICUs (n = 120) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU type | ||||

| Medical-surgical | 78 (59.5) | 87 (57.6) | 86 (58.9) | 70 (58.3) |

| Specialty/other | 53 (40.5) | 64 (42.4) | 60 (41.1) | 50 (41.7) |

| Hospital bed size | ||||

| < 100 | 21 (16.0) | 20 (13.2) | 14 (9.6) | 6 (5.0) |

| 100-249 | 40 (30.5) | 42 (27.8) | 37 (25.3) | 18 (15.0) |

| 250-499 | 19 (14.5) | 25 (16.6) | 33 (22.6) | 36 (30.0) |

| ≥ 500 | 25 (19.1) | 41 (27.2) | 46 (31.5) | 46 (38.3) |

| Missing | 26 (19.8) | 23 (15.2) | 16 (11.0) | 14 (11.7) |

| Teaching hospitals | 20 (15.3) | 24 (15.9) | 30 (20.5) | 33 (27.5) |

Table 2: Characteristics of participating Intensive Care Units, categorized by ICU acuity level. This table provides a breakdown of ICU types, hospital sizes, and teaching status across the different acuity quartiles, highlighting the diversity within the study sample.

Adherence to VTE and stress ulcer prophylaxis was generally high across all acuity levels (96.6% and 90.5% respectively). Adjusted analyses revealed consistently high adherence rates without significant differences between ICU acuity categories (e-Fig 1, e-Table 1, e-Appendix 1 in the original article’s supplementary materials). However, potentially harmful events like sustained hyperglycemia and liberal transfusion practices showed greater variability across ICUs. Adjusted analyses for hypoglycemia, sustained hyperglycemia, and liberal transfusion practices indicated that patients in low-, medium-, and high-acuity ICUs were more likely to experience hypoglycemia and sustained hyperglycemia compared to those in the highest acuity ICUs. For liberal transfusion practices, there was a dose-dependent relationship, with increasing ICU acuity associated with lower odds of such practices (Table 3).

Table 3.

ICU Acuity and Odds of Experiencing Hypoglycemia, Sustained Hyperglycemia, or Liberal Transfusion Practices

| ICU Acuity | Hypoglycemia (n = 1,037,023) | Hyperglycemia (n = 1,037,023) | Transfusion (n = 46,229) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| High | 1.10 (1.05-1.15) | 1.05 (1.03-1.07) | 1.08 (0.98-1.18) |

| Medium | 1.11 (1.05-1.18) | 1.04 (1.02-1.06) | 1.41 (1.25-1.59) |

| Low | 1.12 (1.04-1.19) | 1.07 (1.04-1.10) | 1.55 (1.33-1.82) |

Table 3: Adjusted odds ratios for hypoglycemia, sustained hyperglycemia, and liberal transfusion practices across different ICU acuity levels. This table highlights the increased likelihood of these adverse events in lower acuity ICUs compared to the highest acuity ICUs.

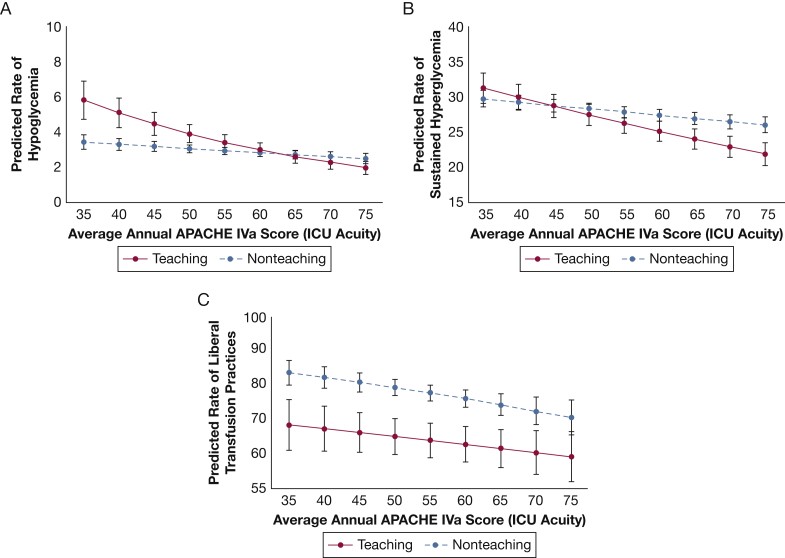

Post hoc analysis, treating ICU acuity as a continuous variable and considering teaching status interaction, revealed that low-acuity teaching hospitals had a higher predicted probability of hypoglycemia and sustained hyperglycemia than low-acuity non-teaching hospitals. As ICU acuity increased, this probability decreased, with a more pronounced effect in teaching hospitals (Figure 2A and 2B). Conversely, teaching hospitals exhibited a lower predicted probability of liberal transfusion practices across all ICU acuity levels (Figure 2C). Analyses restricted to low-risk patients showed similar trends for transfusion outcomes, but no significant differences in hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia across acuity levels.

Figure 2.

Figure 2: Predicted rates of adverse events based on ICU acuity and teaching hospital status. Graphs illustrate the expected rates of (A) hypoglycemic events, (B) sustained hyperglycemia, and (C) liberal transfusion practices relative to ICU acuity, comparing teaching and non-teaching hospitals. This figure visualizes the complex interplay between ICU acuity, hospital type, and patient safety outcomes.

Discussion

This large-scale retrospective study, analyzing data from ICUs participating in a national telemedicine program, reveals important insights into the relationship between ICU acuity and adherence to evidence-based critical care practices. The findings indicate that while adherence to VTE and stress ulcer prophylaxis is uniformly high across ICUs, higher acuity ICUs demonstrate better performance in avoiding potentially harmful events such as hypoglycemia, sustained hyperglycemia, and liberal transfusion practices. This suggests that high-acuity ICUs may be more successful in implementing systems and protocols that promote consistent application of evidence-based guidelines, leading to enhanced patient safety.

The observed superior adherence to certain evidence-based practices in high-acuity ICUs may serve as an indicator of overall high-quality care. It is plausible that ICUs excelling in these measured processes also perform better in other, unmeasured aspects of care, such as care coordination, communication, and quality improvement infrastructure. This aligns with the concept that adherence to evidence-based processes can be a marker for a broader culture of quality and patient safety within an institution. The study reinforces the value of utilizing a comprehensive set of performance measures, encompassing structure, process, and outcomes, to effectively assess and improve ICU quality. Further research, particularly employing mixed-methods approaches to study high-performing ICUs, is warranted to identify and disseminate best practices that contribute to outstanding outcomes in critical care settings.

The study’s findings also contribute to the ongoing discussion regarding the volume-outcome relationship in critical care. While previous research has indicated that high-volume centers may be associated with better outcomes, this study highlights the independent role of ICU acuity. The association between ICU acuity and adherence to evidence-based practices, irrespective of ICU volume, provides further nuance to the understanding of factors influencing ICU performance. This information is valuable for informing decisions related to regionalization of critical care services and identifying organizational factors that contribute to superior ICU performance.

The consistently high adherence to VTE and stress ulcer prophylaxis across ICUs in this study, particularly within a telemedicine program, is noteworthy. It aligns with previous research suggesting that telemedicine interventions in ICUs can improve adherence to evidence-based practices. The telemedicine model, with its emphasis on remote intensivist oversight, real-time performance monitoring, and implementation of standardized protocols, may contribute to the widespread adoption of these foundational preventive measures.

The exploratory analysis revealing the interaction between teaching status and ICU acuity adds another layer of complexity. The observation that low-acuity teaching hospitals exhibit higher rates of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia compared to non-teaching hospitals, with this trend reversing at higher acuity levels, warrants further investigation. Potential explanations include differences in glucose management protocols, the roles of trainees and specialists in glucose control, and variations in the organizational structures of teaching versus non-teaching hospitals. Similarly, the lower rate of liberal transfusion practices in teaching hospitals, regardless of acuity, may reflect a greater emphasis on evidence-based transfusion guidelines and a more specialized physician workforce. These findings underscore the need for further research into the organizational and operational factors within different hospital types and acuity levels that influence the implementation of evidence-based practices and patient outcomes.

This study is subject to certain limitations. The cohort, while diverse, is drawn from ICUs participating in a telemedicine program, which may limit generalizability to ICUs outside of such programs. Data on other hospital characteristics and organizational factors were not available, potentially limiting the ability to fully account for confounding variables. The reliance on chart documentation for outcome assessment introduces the possibility of misclassification bias. Finally, the method of calculating average daily glucose based on potentially single daily measurements may not capture the full glycemic variability in some patients.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates a significant association between ICU acuity and adherence to evidence-based practices in critical care. Specifically, higher acuity ICUs exhibit better performance in avoiding potentially harmful events, suggesting a more effective implementation of standardized, evidence-based processes. These findings emphasize the importance of understanding the organizational characteristics and operational strategies of high-acuity ICUs to identify targets for improving the quality of critical care across all ICU acuity levels. Future research should focus on dissecting the specific factors within high-acuity ICUs that contribute to their success in implementing evidence-based medicine and translating these insights into actionable strategies for quality improvement in all critical care settings.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: K. C. V., J. Y. S., and O. B. had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. K. C. V., O. B., M. O. H., C. G. S., and M. P. K. contributed to the conception and design of this study. O. B. contributed to data acquisition. K. C. V. and J. Y. S. contributed to the analysis of data. K. C. V., J. Y. S., O. B., M. O. H., C. G. S., D. R. S., and M. P. K. contributed to interpretation of data. All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; have contributed to drafting the article for important intellectual content; and have provided final approval of the version to be published.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: O. B. is an employee of Philips Healthcare. None declared (K. C. V., J. Y. S., M. O. H., C. G. S., D. R. S., M. P. K.).

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Other contributions: This article was reviewed and approved by Craig Lilly, MD; Louis Gidel, MD, PhD; Richard Riker, MD; Leo Celi, MD, MS, MPH; Teresa Rincon, RN, BSN, eCCRN; Theresa Davis, PhD, RN, NE-BC, CHTP; and Michael Waite, MD of the Philips eICU Research Institute Publications Committee. They were not compensated for this review.

Additional information: The e-Appendix, e-Figures and e-Table can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The Department of Veterans Affairs did not have a role in the conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of data; or in the preparation of the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US Government.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: Dr Vranas is supported by grant 5K12HL133115. Dr Harhay is supported by grants K99HL141678 and R00HL141678. Dr Slatore is supported by resources from the VA Portland Health Care System. Dr Sullivan is supported by grant K07CA190706.

Supplementary Data

e-Online Data

mmc1.pdf (220KB, pdf)