1. INTRODUCTION

In Austria, a significant majority, nearly 70%, of individuals spend their final days in institutional settings such as hospitals or long-term care facilities (Statistics Austria, 2020). This reality underscores the critical need for robust end-of-life (EoL) care within these institutions. Globally, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated in 2011 that over 19 million people required palliative care during their EoL phase (WHO 2014 Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life). To enhance these services, organizations like the NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) have issued guidelines recommending reviews of current services and referrals to specialized palliative care, especially for patients with non-cancer diagnoses who require holistic needs assessments and advanced care planning.

However, the provision of effective EoL care is often hindered by several challenges, as highlighted in scientific literature. These include policy and guideline gaps, insufficient advanced care planning, inadequate staff training and experience, and prognostic uncertainties (Omar Daw Hussin et al., 2018; Threapleton et al., 2017). A primary obstacle is the timely and accurate recognition of the EoL phase itself (Bamford et al., 2018).

This study addresses the crucial aspect of care needs in the terminal phase of life. By delving deeper into the care dependencies of individuals nearing the end of life, we aim to provide healthcare professionals and researchers with a clearer understanding to improve the quality and delivery of EoL care.

2. BACKGROUND: The Significance of Dependency in Palliative Care

Physical decline is a hallmark of the end-of-life journey (Stow et al., 2019). This is particularly pronounced in geriatric patients with chronic conditions, often resulting in substantial care needs (Finucane et al., 2017). These needs encompass not only symptom management, such as pain control, but also vital social and emotional support for patients and their families (Santivasi et al., 2020). Early identification of patients in their last phase of life is crucial to effectively address these complex needs.

Historically, palliative care and hospice programs have predominantly focused on cancer patients. However, it’s now widely recognized that the majority of individuals requiring palliative care are older adults with non-malignant conditions (WPCA, 2014). Identifying the palliative care requirements for these patients is more challenging due to the often unpredictable progression of non-malignant diseases. The ambiguity between palliative and EoL care further complicates practical application (Amblàs‐Novellas et al., 2016; Dalkin et al., 2016).

While the WHO (2020) defines palliative care as improving the quality of life for patients and families facing life-threatening illnesses, a universally accepted definition of “end of life” remains elusive. This definitional gap can lead to inadequate EoL care, such as insufficient pain management (Dalkin et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2018; Hui et al., 2014). Patients with dementia are especially vulnerable, with their EoL care needs frequently overlooked (Hill et al., 2018).

Functional and physical decline intensifies during the terminal phase, suggesting a high degree of care dependency (Amblàs‐Novellas et al., 2016; Stabenau et al., 2015). Age and disease significantly impact individual care needs (Caljouw et al., 2014; Edjolo et al., 2016). Various concepts describe these needs, including frailty, functional decline, disability, and care dependency.

Care dependency, a specific nursing concept developed by Dijkstra (1998), refers to “a process in which professional support is offered to a patient with decreased self-care abilities and significant care demands, aiming to restore independence in self-care” (Dijkstra et al., 1996). This concept is operationalized using Virginia Henderson’s nursing theory (1966), which addresses 14 fundamental human needs encompassing physical, psychosocial, and spiritual dimensions.

The Care Dependency Scale (CDS) is a multidimensional assessment tool used to measure care dependency. It provides a holistic approach by assessing physical and psychosocial needs (Piredda et al., 2020; Piredda, Bartiromo, et al., 2016; Piredda, Biagioli, et al., 2016). Despite its suitability, care dependency has been underutilized in EoL care research. The CDS’s holistic approach, grounded in Henderson’s 14 human needs—which explicitly include terminal care—makes it particularly relevant for describing the needs of individuals in their final phase of life.

Experiencing dependency profoundly impacts individuals (Piredda, Bartiromo, et al., 2016; Piredda, Biagioli, et al., 2016. It can alter their life perspectives and self-perception as care recipients. Studies on advanced cancer patients reveal that care dependency can shift their perception of time and priorities, emphasizing emotions like love as paramount (Piredda, Bartiromo, et al., 2016; Piredda, Biagioli, et al., 2016). While most people desire independence, especially at life’s end (Delgado‐Guay et al., 2016; Horne et al., 2012), functional decline and diverse care needs are inevitable in the EoL phase (Schmidt et al., 2018; Stabenau et al., 2015). A deeper understanding of care dependency in EoL situations allows healthcare providers to deliver more effective, holistic care, enhancing patient quality of life, the central aim of EoL palliative care.

This study aimed to assess and characterize the key aspects of “care dependency” in patients and residents at the end of life. The research questions guiding this study were:

- To what degree and in which specific areas of care dependency are patients and residents most dependent at the end of life?

- What factors significantly influence care dependency in these individuals?

3. METHODOLOGY

This study utilized data from the Austrian Nursing Quality Measurement 2.0, a cross-sectional multicenter study conducted in 2017. This annual study, performed across several European countries, employs a standardized questionnaire (Nie‐Visser et al., 2013). In 2017, data collection occurred in Austrian hospitals, geriatric hospitals, and nursing homes on a single day, with voluntary institutional participation.

The measurement, in collaboration with Maastricht University, focused on quality indicators like continence, malnutrition, falls, restraints, pain, and care dependency (Eglseer et al., 2018; Institute of Nursing Science, 2020). The study adhered to the STROBE guideline for observational studies (Supplementary File S1).

3.1. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire, developed and regularly updated by Maastricht University, is based on Donabedian’s Model of Quality (structure, process, outcome). It gathers data on institutions, hospital wards, and patients/residents, including demographics, medical diagnoses, and nursing care problems such as pain, pressure ulcers, falls, and malnutrition. Since 2017, the German version includes the question: “Is the client on a pathway for management of patients at the EoL?” The accompanying manual defines EoL as extending from several days to a year before expected death, requiring interdisciplinary team consensus.

Care dependency was measured using the German version of the CDS, a validated and reliable instrument (Dijkstra et al., 1996; Lohrmann et al., 2003b). The CDS has been adapted and validated across various settings and patient groups (Dijkstra et al., 1999, 2000, 2002; Kottner et al., 2010; Lohrmann et al., 2003b; Piredda, Bartiromo, et al., 2016; Piredda, Biagioli, et al., 2016; Tork et al., 2008). It assesses physical and psychosocial care dependency, with psychosocial items including day/night patterns, communication, social contact, and understanding rules and values (Piredda et al., 2020; Piredda, Bartiromo, et al., 2016; Piredda, Biagioli, et al., 2016).

The CDS comprises 15 items, each scored from 1 (completely dependent) to 5 (completely independent). Summing item scores yields a total score, categorizing patients into five dependency levels: completely dependent (0–24), greatly dependent (25–44), partially dependent (44–59), largely independent (60–69), and independent (>69) (Dijkstra et al., 2006; Doroszkiewicz et al., 2018).

3.2. Data Collection Process

Nurses at participating institutions received training and written materials before data collection. On a scheduled date, data was collected by teams of two nurses—one from the ward and another from a different ward. They jointly completed questionnaires for each patient, reaching consensus through discussion. In case of disagreement, the “independent” nurse’s response prevailed. Manuals and a hotline to the Austrian Nursing Quality Measurement team were available for clarification.

3.3. Sample Population

Austrian inpatient healthcare institutions with over 50 beds were invited to participate. Forty-three institutions (37 hospitals, 2 geriatric hospitals, and 4 nursing homes) participated on November 14, 2017. 3,589 patients and residents provided informed consent. Of these, 389 were identified as EoL patients based on a positive answer to “Is the client on a pathway for management of patients at the EoL?”, a decision made by the interdisciplinary team before the measurement.

3.4. Data Analysis Techniques

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 26; IBM Corp., 2019). Descriptive statistics characterized the sample. Chi-square tests assessed differences between EoL and non-EoL groups.

Care dependency was analyzed using total CDS scores and item-level scores. Item-level analysis used medians. Chi-square tests for nominal data (diagnoses, sex) and Mann–Whitney U tests for parametric data (age) were used for statistical significance. Correlation coefficients between CDS items and potential influencing factors were calculated.

3.5. Binomial Logistic Regression Modeling

Binomial logistic regression was conducted for each CDS item. The five dependency groups were recoded into a dichotomous variable: “highly dependent” (completely or greatly dependent) versus “partially or not care dependent” (partially, largely, or completely independent). Univariate logistic regression identified significant independent variables (from literature and descriptive analysis of variables differing significantly between EoL and non-EoL patients). Multivariate models were then built using variables significant in univariate analysis (p<0.05).

3.6. Ethical Considerations

The study received ethical approval from the Medical University of Graz (EK‐Number: 20‐192 ex 08/09). All participants provided written informed consent. Informed consent processes were adapted for hospitals and long-term care facilities to accommodate proxy consent for patients unable to consent themselves.

4. FINDINGS

4.1. Participant Demographics

Of the total sample (N = 3589), 389 (10.8%) were on an EoL pathway. Most EoL patients/residents were in geriatric institutions. 43% of EoL patients had dementia. Musculoskeletal, circulatory system diseases, and dementia were the most frequent diagnoses among 27 queried (Table 1). Cancer diagnosis was also noted for its potential impact on care dependency. EoL patients significantly differed from non-EoL patients in age, sex, institution type, and diagnoses (p<0.001) except for cancer diagnosis (p=0.048).

TABLE 1. Descriptive statistics comparing EoL and non-EoL patients and residents

| Characteristic | EoL (n = 389) | Non-EoL (n = 3200) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% female) | 65% | 53% | |

| Age (Mean (SD)) | 78 (16) | 68 (17) | |

| Institution Type (% Hospital) | 34.5% | 93% | |

| Institution Type (% LTC/Geriatric) | 65.5% | 7% | |

| Diseases of Circulatory System (%) | 68.6% (267) | 47.8% (1528) | |

| Diseases of Musculoskeletal System (%) | 43.2% (168) | 25% (802) | |

| Dementia (%) | 43.2% (168) | 7.5% (239) | |

| Cancer/Neoplasm (%) | 20.3% (79) | 16% (523) | .048 |

4.2. Care Dependency in EoL Patients: Descriptive Analysis

Analysis of CDS scores revealed that 60% of EoL patients/residents were completely or greatly care dependent, compared to only 12% of non-EoL patients.

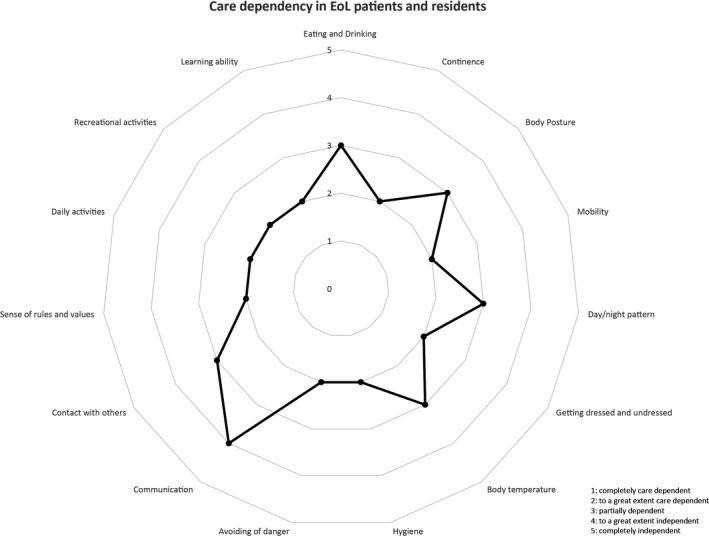

Item-level analysis showed EoL patients/residents were greatly dependent in learning ability, recreational activities, daily activities, sense of rules and values, social contact, hygiene, continence, and danger avoidance (Figure 1), indicating a high overall care dependency level.

FIGURE 1. Care Dependency in EoL Patients and Residents on an Item Level

Using the dichotomized care dependency variable, patients with dementia or circulatory system diseases showed significantly higher care dependency across all CDS items (p<0.05).

Correlation analysis showed weak to moderate correlations between CDS item scores and sex, age, dementia, cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal diseases, and cancer. CDS sum score correlations were: age, −0.480 (p<0.01); dementia, −0.581 (p<0.01); circulatory system diseases, −0.154 (p<0.01); and musculoskeletal diseases, −0.148 (p<0.01).

4.3. Binary Regression Analysis of EoL Patient Data

Regression analysis aimed to identify predictors of high care dependency. Age and dementia were significant predictors for increased likelihood of high dependency across all CDS items (Table 2). Dementia particularly increased this likelihood. Only for daily activities, circulatory system diseases also increased the likelihood of high care dependency. Cancer and musculoskeletal diseases were not significant predictors.

TABLE 2. Care Dependency in EoL Patients and Residents on an Item Level (Regression Analysis)

| CDS Item | Predictor | B | SE B | Wald X² | p | Exp (B) | 95% CI for Exp (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating and drinking | Age | .04 | .01 | 16.11 | .00 | 1.04 | 1.02 – 1.06 |

| Dementia | 1.21 | .24 | 24.62 | .00 | 3.36 | 2.08 – 5.42 | |

| Incontinence | Age | .04 | .01 | 15.49 | .00 | 1.04 | 1.02 – 1.06 |

| Cancer | 1.18 | .26 | 2.69 | .00 | 3.25 | 1.96 – 5.40 | |

| Body position | Age | .03 | .01 | 8.50 | .00 | 1.03 | 1.01 – 1.05 |

| Dementia | 1.01 | .24 | 17.97 | .00 | 2.75 | 1.72 – 4.39 | |

| Mobility | Age | .04 | .01 | 13.29 | .00 | 1.04 | 1.02 – 1.06 |

| Dementia | .87 | .24 | 13.31 | .00 | 2.38 | 1.49 – 3.78 | |

| Day and night patterns | Age | .02 | .01 | 5.25 | .02 | 1.02 | 1.00 – 1.05 |

| Dementia | 1.17 | .25 | 22.53 | .00 | 3.21 | 1.98 – 5.20 | |

| Getting dressed/undressed | Age | .04 | .01 | 17.28 | .00 | 1.04 | 1.02 – 1.06 |

| Dementia | 1.27 | .27 | 21.70 | .00 | 3.57 | 2.09 – 6.09 | |

| Body temperature | Age | .03 | .01 | 8.75 | .00 | 1.03 | 1.01 – 1.05 |

| Dementia | 1.40 | .25 | 32.65 | .00 | 4.05 | 2.51 – 6.55 | |

| Hygiene | Age | .05 | .01 | 19.37 | .00 | 1.05 | 1.03 – 1.07 |

| Dementia | 1.40 | .29 | 22.77 | .00 | 4.06 | 2.28 – 7.21 | |

| Avoidance of danger | Age | .05 | .01 | 18.40 | .00 | 1.05 | 1.03 – 1.07 |

| Dementia | 1.89 | .29 | 43.19 | .00 | 6.59 | 3.75 – 11.56 | |

| Communication | Age | .02 | .01 | 2.49 | .11 | 1.02 | 1.00 – 1.04 |

| Dementia | 1.12 | .26 | 19.37 | .00 | 3.08 | 1.87 – 5.08 | |

| Contact with others | Age | .03 | .01 | 7.92 | .00 | 1.03 | 1.01 – 1.05 |

| Dementia | 1.59 | .25 | 4.78 | .00 | 4.90 | 3.01 – 7.98 | |

| Sense of rules and values | Age | .03 | .01 | 6.32 | .01 | 1.03 | 1.01 – 1.05 |

| Dementia | 1.92 | .26 | 54.07 | .00 | 6.81 | 4.08 – 11.35 | |

| Daily activities | Age | .03 | .01 | 1.16 | .00 | 1.03 | 1.01 – 1.06 |

| Dementia | 2.17 | .29 | 54.91 | .00 | 8.77 | 4.94 – 15.58 | |

| D. o. Circulatory S. | .53 | .31 | 2.85 | .09 | 1.69 | 0.92 – 3.12 | |

| Recreational activity | Age | .02 | .01 | 4.87 | .03 | 1.02 | 1.00 – 1.04 |

| Dementia | 1.93 | .26 | 53.49 | .00 | 6.88 | 4.10 – 11.53 | |

| Learning ability | Age | .03 | .01 | 6.66 | .01 | 1.03 | 1.01 – 1.05 |

| Dementia | 2.47 | .31 | 64.86 | .00 | 11.76 | 6.46 – 21.42 | |

| D. o. Circulatory S. | .72 | .32 | 4.91 | .03 | 2.04 | 1.09 – 3.85 |

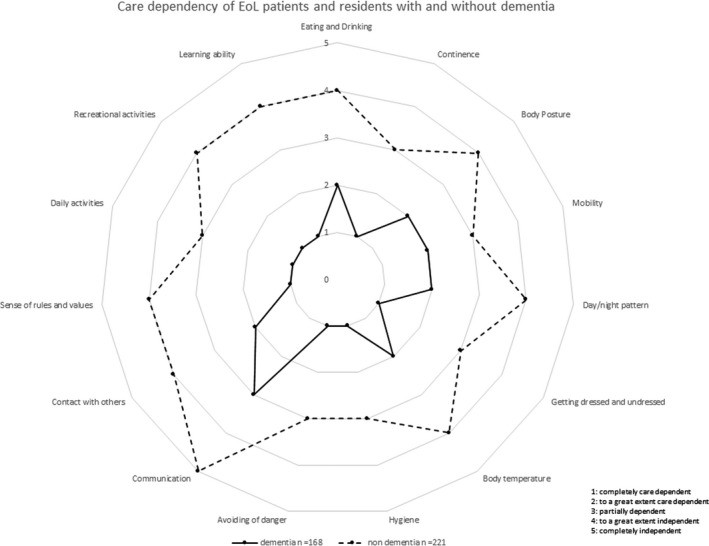

Stratification by dementia diagnosis revealed that EoL patients with dementia (n=168) showed significantly higher care dependency (p<0.001) than those without (n=221). EoL patients with dementia were completely care dependent in learning ability, recreational activities, daily activities, sense of rules and values, danger avoidance, hygiene, dressing/undressing, and continence (Figure 2), primarily physical care dependency items.

FIGURE 2. Care dependency of EoL patients and residents with and without dementia

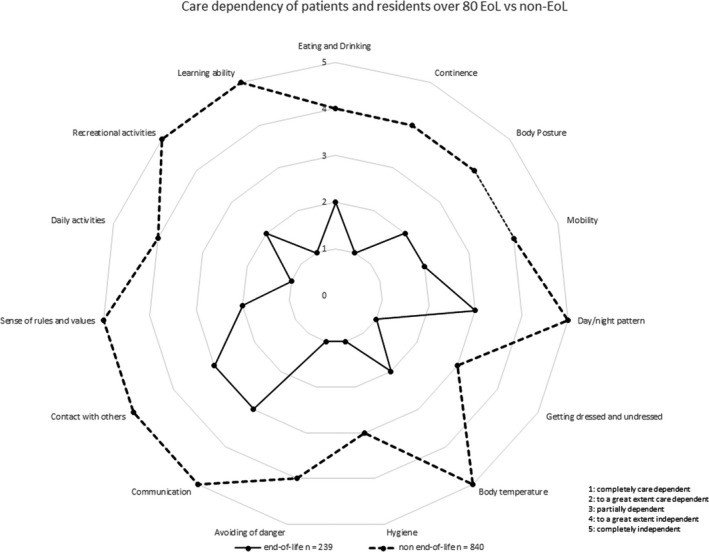

Comparing EoL and non-EoL patients aged 80 and over, significant differences in care dependency remained (p<0.001) (Figure 3), although non-EoL patients over 80 were generally more independent than EoL patients in the same age group.

FIGURE 3. Care dependency of EoL and non-EoL patients and residents aged 80 years and older

5. DISCUSSION

The study sample showed significant differences between EoL and non-EoL patients/residents in age, sex, and diagnoses. EoL patients were older and more likely to have dementia and circulatory system diseases. Age and dementia were major influencers of care dependency in EoL patients. Comparison of EoL and non-EoL patients over 80 highlighted that age alone does not equate to high care dependency; being in the EoL phase is a critical factor.

The influence of age on care dependency is consistent with previous research (Dijkstra et al., 2012; Lohrmann et al., 2003a, and dementia’s strong impact aligns with findings by Schüssler et al. (2015). Our study reinforces that dementia and EoL status are key determinants of care dependency, affecting nearly all CDS items. Even EoL patients without dementia exhibit higher dependency compared to non-EoL individuals, but are more independent than EoL patients with dementia.

These findings underscore that care needs in the EoL phase, especially with dementia, differ significantly from other patient groups (Finucane et al., 2017; van der Steen et al., 2017). A major challenge in geriatric palliative care is recognizing the EoL phase onset, particularly in non-cancer patients (Bamford et al., 2018; Dwyer et al., 2008; Flierman et al., 2019; Smets et al., 2018). Bern-Klug (2004) described “ambiguous dying syndrome” in older adults, hindering access to necessary emotional and spiritual care (Lloyd et al., 2011).

Patients with dementia have unique EoL care needs (McCleary et al., 2018), requiring more time for care due to communication challenges and behavioral symptoms. Touch becomes a vital communication method (McCleary et al., 2018). Our study showed communication as an area of partial dependency in EoL patients. Understanding palliative care trajectories in dementia, characterized by prolonged gradual decline (Finucane et al., 2017; Murray et al., 2005), is crucial for improving care. Boyd et al. (2019) advocate for complex, integrated palliative care in long-term facilities for dementia patients, potentially years before death. Our data highlights high care dependency in physical needs like continence, learning, recreation, daily activities, danger avoidance, and hygiene for EoL patients.

Addressing specific care needs is paramount. Item-level analysis showed consistent dependency across EoL patients (with and without dementia, and over 80 years) in learning ability, recreation, daily activities, rules/values, danger avoidance, hygiene, dressing, and continence. These align with symptoms observed in dementia’s terminal phase, such as mobility issues, pain, and feeding problems (Koppitz et al., 2015).

6. CONCLUSION

This study concludes that a “typical” geriatric EoL patient or resident is often female, elderly, and diagnosed with dementia and/or circulatory system disease, resulting in significant physical and psychosocial care dependency. Increased care dependency can serve as an indicator of entering the EoL phase.

Detailed characterization of the EoL phase is valuable for nurses, enhancing their awareness and enabling targeted, effective EoL care in clinical practice. The Care Dependency Scale proves to be a useful dependency tool in palliative care, aiding in the identification and management of patient needs.

6.1. Limitations

The study’s primary limitation is the subjective EoL patient identification by healthcare professionals. The EoL patient sample size is also relatively small.

6.2. Recommendations

Further research is needed to develop more precise methods for identifying geriatric patients requiring palliative and EoL care, ensuring optimal care in their final phase of life. Defining the onset of the EoL phase more clearly is essential (Schüttengruber et al. paper submitted).

6.3. Relevance to Clinical Practice

The findings can assist clinicians in identifying EoL patients/residents more effectively and recognizing their specific care needs, particularly physical needs. This supports a more holistic approach to EoL palliative care.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Supplementary Material: Click here for additional data file. (29.2KB, docx)

Schüttengruber, G. , Halfens, R. J. G. , & Lohrmann, C. (2022). Care dependency of patients and residents at the end of life: A secondary data analysis of data from a cross‐sectional study in hospitals and geriatric institutions. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 31, 657–668. 10.1111/jocn.15925

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author, subject to privacy and ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

[Please refer to the original article for the complete list of references.]

Associated Data

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material: Click here for additional data file. (29.2KB, docx)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the corresponding author, subject to privacy and ethical restrictions.