Nursing homes, also known as long-term care facilities, are increasingly becoming the final residence for individuals managing chronic, life-limiting conditions. The complexity and medical needs of residents entering these facilities are on the rise. Current data indicates that many residents pass away within two years of admission, with a significant majority spending their final days in long-term care. This reality places a critical responsibility on care providers to deliver high-quality end-of-life care. To ensure and improve this care, nursing home administrators require effective tools to objectively measure the quality of care provided at the end of life. This need for objective data to evaluate current practices and identify areas for improvement underscores the importance of systematic assessment methods such as chart audits. Chart audits are valuable tools designed to enhance patient care by pinpointing gaps in service through structured data collection and analysis. They are routinely utilized across various healthcare settings to monitor and improve patient outcomes.

While chart audits have been employed to evaluate palliative care quality in hospitals, primary care settings, and hospice/home care environments, their application in nursing homes remains limited. A review of existing research reveals a scarcity of studies using chart audits to assess end-of-life care specifically within nursing homes. The few studies identified often focus narrowly on the immediate period preceding death. Crucially, there is a gap in research and tools designed for routine clinical practice in long-term care that encompass the entire dying trajectory. Excellence in palliative and end-of-life care necessitates addressing the physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs of individuals for a period extending beyond the very final moments of life. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the care a resident receives throughout their entire dying process is essential to truly gauge the quality of end-of-life care provided.

To address these limitations and create a clinically relevant assessment instrument, this study focused on the development and testing of an empirically derived chart audit tool for long term care, specifically designed to evaluate care delivery throughout the entire dying trajectory. The primary objectives were threefold: (1) to identify key indicators of quality end-of-life care relevant for inclusion in a chart audit tool; (2) to develop, validate, and refine a nursing home resident end-of-life audit tool based on these indicators; and (3) to assess the practicality and usefulness of this tool in real-world clinical settings.

Methods

A three-phase mixed-methods study was conducted to meet the outlined objectives. Adopting the methodology established by Steiner and Norman for the development and validation of health measurement scales, the research team implemented a structured process encompassing: 1) a thorough review of existing literature; 2) generation of potential audit items; 3) item selection and validity assessment; 4) field trials to test the tool; and 5) refinement of the instrument into its final form. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the University of Manitoba Education/Nursing Research Ethics board, ensuring adherence to ethical research standards.

Phase I: Item Generation

The initial phase of the study was dedicated to generating a comprehensive list of potential data elements for the chart audit tool. These elements were intended to reflect best practices in end-of-life care for nursing home residents. Leveraging the expertise of the research team and conducting a critical review of the literature on best practices in nursing home end-of-life care, the framework for a “good death” proposed by Bosek and colleagues was utilized. This framework provided broad categories under which to organize potential audit items, including: pain and symptom management, clear decision-making processes, preparation for death, and affirmation of the person as a whole. The timeframe for evaluating end-of-life care was determined through literature review. The team also examined existing audit tools used within the local regional health authority to establish a template for item range, question formatting, and optimal data collection methods using an audit tool format.

Phase I Analysis: Synthesis of Initial Items

Following the methodology recommended by Gearing and colleagues, the data gathered in Phase I was systematically coded, categorized, and synthesized. This process ensured that the items considered for the draft audit tool were: 1) representative of the experiences associated with a good death in the nursing home context, encompassing common occurrences and areas of significant concern; 2) organized under the key conceptual domains identified in the literature review; and 3) inclusive of both quantitative and qualitative items to capture the nuances of care provided in the last month and week of life. For example, simple yes/no questions were designed to identify the presence of specific symptoms, while open-ended text areas were included to record details of psychosocial support provided to families. Based on team consensus and guided by the literature, it was decided that the audit tool would assess care provided during the resident’s last month of life. The tool’s format was designed following recommendations from Allison and Banks, emphasizing accuracy in data capture and minimizing the likelihood of missing data, crucial for effective chart audits.

Phase II: Development, Validation, and Refinement

Phase II focused on the development, validation, and refinement of the chart audit tool. A convenience sample of key decision-makers and clinicians specializing in gerontology and palliative care, all involved in nursing home resident care (either in direct clinical roles or administrative capacities), were recruited to participate in a focus group. The goal of the focus group was to gather feedback on the clarity, content, and scope of the draft audit tool.

Administrative staff from a large urban regional health authority long-term care program in central Canada facilitated recruitment by sending invitation letters via email to potential focus group participants. Interested individuals were instructed to contact the study’s research assistant directly. The research assistant verified eligibility, addressed any questions about the study, and provided details regarding the focus group’s logistics. Participants were also provided with a copy of the draft chart audit tool to review before the session. Prior to the discussion, participants signed consent forms and completed demographic questionnaires, ensuring ethical and informed participation.

During the focus groups, participants were encouraged to share their insights and concerns regarding the audit tool. Each question was systematically reviewed to assess its clarity, relevance, and importance in evaluating end-of-life care. The focus group was led by the first author, with detailed notes taken by the research assistant to capture all feedback. The session lasted approximately 45 minutes. Feedback collected on clarity, relevance, and item importance, as well as any broader concerns, was used to revise the tool. The final version of the tool was then reviewed by the research team to ensure item accuracy and appropriate formatting before moving to pilot testing.

Phase II Analysis: Expert Appraisal

The focus groups provided critical appraisal of the draft audit tool by a group of gerontological and palliative care healthcare providers and administrators (n=12). Participants had an average age of 47 years (median 49 years), with substantial professional experience averaging 23.95 years (range 8–37 years), and an average of 11.95 years working specifically in long-term care (range 2–26 years). The group comprised registered nurses (n=5), clinical nurse specialists (n=2), a social worker (n=1), a pharmacist (n=1), and long-term care administrators (n=3), representing a diverse range of expertise. All items on the audit tool received strong endorsement from the group, including the chosen assessment period (last month of life). Minor revisions were made to instrument questions to refine terminology (e.g., regarding advance care planning and levels of care) and to improve formatting based on feedback from the research team, ensuring the tool was user-friendly and clinically accurate.

Phase III: Pilot Testing

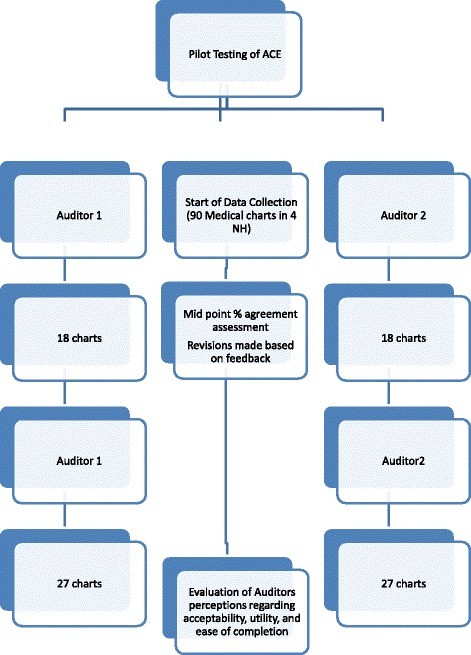

The final phase involved a pilot trial of the audit tool to evaluate its reliability, completion time, acceptability, and overall utility (See Fig. 1). Four nursing home facilities participated in the testing, from which a random sample of 20% (n=90) of deceased residents’ charts from January to December 2012 were audited. This sample size aligns with recommendations for chart audit studies. Two chart auditors with clinical backgrounds in palliative care and gerontology were trained in the use of the audit tool. To assess for any ambiguity or confusion in the tool, the auditors independently extracted data from four identical charts from the overall sample. The abstracted data was compared to identify areas of agreement and disagreement on key variables. Any discrepancies were reviewed using the original chart information as the definitive reference, facilitating detailed discussion and clarification. A primary challenge identified was that assessing symptom management across the last month of life required extensive data abstraction, leading to an unacceptably long average completion time of 73 minutes per audit. Following discussions between the auditors and research team, the symptom management assessment period was adjusted to focus on the last week of life, while the remaining items continued to assess care provided in the last month.

Fig. 1.

Phase III protocol flow chart depicting participant recruitment, chart audit process, and data analysis steps for the ACE instrument validation.

Phase III protocol flow chart depicting participant recruitment, chart audit process, and data analysis steps for the ACE instrument validation.

Once consensus was achieved between the chart auditors and research team regarding the clarity of the items, the auditors independently audited 18 of the same charts to formally assess inter-rater reliability. After analyzing these charts, each auditor independently audited a sub-sample of the remaining charts (n=58). Throughout the pilot testing, each auditor maintained a journal to record any difficulties encountered, suggestions for tool refinement, and overall impressions of the tool’s ease of use.

Phase III Analysis: Reliability and Usability

The reliability of the chart audit tool was assessed by calculating percentage agreement. This method was chosen because Cohen’s kappa (Kappa), another measure of inter-rater reliability, can be unreliable when data is skewed, such as when raters frequently select the same response categories, resulting in artificially low reliability scores. Percentage agreement was calculated based on the number of matching ratings on the 18 charts audited at the midpoint of the study. For each item on the instrument, a percentage agreement of 80% or higher was considered to indicate acceptable reliability. The average time to complete a chart audit was calculated based on the total time taken to extract data from each chart and the total number of charts reviewed. Journal notes from the auditors and meeting minutes with the research team were analyzed for major themes using content analysis and constant comparative techniques to assess the acceptability, utility, and ease of use of the chart audit tool.

Results

The final instrument was named the Auditing Care at the End of Life (ACE) instrument. It comprises 27 questions organized across 6 domains (Table 1). These domains were conceptually derived from the literature review, encompassing key aspects of end-of-life care (symptom occurrence and management; acknowledgment of and preparation for dying; evidence of advance care planning; attention to spiritual health and cultural considerations). Additional domains were included to provide context for the audited care, such as resident demographics and factors surrounding the death (e.g., place of death, cause of death, hospitalizations). Within each of these six domains, questions were developed to capture best practices in end-of-life care delivery.

Table 1.

Example ACE tool domains and questions

| Domain 1: Demographics |

|---|

| ● Date of birth ● Date of death ● Gender ● Length of NH stay (in months) |

| Domain 2: Situation around death |

| ● Indication on health record that death was expected? (YES/NO) ● Place of death (NH/Chronic Care/Acute Care/Palliative Care Unit) ● Was the resident transfered to acute care in their last month of life? (YES/NO) |

| Domain 3: Clear decision making |

| ● Was there an Advance Care Plan? (YES/NO) ● Any changes to the Advance Care Plan made at last review? (YES/NO) ● Was there a Health Care Directive (YES/NO) |

| Domain 4: Preparation for death |

| ● Is there evidence in the progress notes that staff recognized changes in the resident’s condition that acknowledged that end of life was near? (YES/NO) ● Were there changes or adjustments made to the resident’s physician/NP orders in the last month of life? (YES/NO) ● Were there any medication changes made in the last week of life? (YES/NO) ● Is there evidence in the progress notes that psychosocial support was provided to family members or friends during the dying experience? (YES/NO) ● Is there evidence in the progress notes of communication with family or friends about end-oflife care? (YES/NO) |

| Domain 5: Spiritual health and cultural aspects of care |

| ● Evidence of resident’s or family wishes regarding rites and rituals, or spiritual considerations acted upon (e.g., minister/pastor called, last rites administered)? (YES/NO) ● Resident’s spiritual health preferences documented? (YES/NO) |

| Domain 6: Symptoms and symptom management through the death |

| ● Is there evidence that Pain was assessed?(YES/NO) ● If a symptom (physical or psychological) is present, describe the managment. ● Personal Care/Comfort Provided in last week of life (e.g.: bathing, mouth care, positioning; incontinence care)?(YES/NO) ● Were consults made for other resources (e.g. Social Work, Volunteers, Clinical Nurse Specialists, Speech Language Pathologist)? (YES/NO) |

In the pilot testing of the ACE instrument, the average time to complete an audit of one resident chart was 28.2 minutes (range: 15–60 minutes). The percentage agreement between raters across the 27 questions on the 18 charts ranged from 61% to 100% (see Table 2). Overall, both auditors found the instrument user-friendly; however, the symptom management section proved to be the most challenging. Auditors reported difficulties in deciphering handwriting in charts, inconsistencies in the use of standardized pain assessment tools (despite pain being noted in progress notes), and a lack of documented follow-up or evaluation of intervention effectiveness (e.g., after administering pain medication).

Table 2.

Percentage agreements between auditors on the ACE items

| Instrument item # | Number of scores in agreement (n = 18) | Percent agreement | Description of question on ACE |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 18 | 100 | Indication on health record death was expected |

| 9 | 18 | 100 | Place of death |

| 10 | 18 | 100 | Was the resident transferred to acute care (ED) in the last month of life? |

| 11 | 18 | 100 | Was there a Health Care Directive? |

| 12 | 18 | 100 | Was there an Advance Care Plan (ACP)? |

| 12a | 17 | 94 | Goals of care chosen |

| 14 | 15 | 83 | Any changes made to the last ACP? |

| 15 | 18 | 100 | Is there evidence that EOL was near? |

| 16 | 16 | 88 | Were there changes to resident’s orders in the last month? |

| 17 | 18 | 100 | Were there medication changes in the last week? |

| 18 | 15 | 83 | Is there evidence of communication with family? |

| 19 | 17 | 94 | Is there evidence that psychosocial support was provided to the family? |

| 20 | 16 | 88 | Resident’s spiritual health preferences documented? |

| 21 | 15 | 83 | Evidence of resident’s or family wishes regarding rites and rituals, spiritual considerations acted upon? |

| 22 | 17 | 94 | Is there evidence that pain was assessed? |

| 24a | 13 | 71 | Pain present? |

| 24b | 18 | 100 | Nausea present? |

| 24c | 16 | 88 | Vomiting present? |

| 24d | 18 | 100 | Constipation present? |

| 24e | 15 | 83 | Diarrhea present? |

| 24f | 17 | 94 | Dysphagia present? |

| 24 g | 15 | 83 | Dyspnea present? |

| 24 h | 15 | 83 | Respiratory congestion? |

| 24i | 14 | 77 | Cough present? |

| 24j | 13 | 72 | Dry mouth present? |

| 24 k | 11 | 61 | Fever present? |

| 24 l | 13 | 72 | Skin breakdown present? |

| 24 m | 17 | 94 | UTI? |

| 24n | 17 | 94 | Edema present? |

| 24o | 18 | 100 | Seizures present |

| 24p | 13 | 72 | Other symptom issues? |

| 24q | 17 | 94 | Depression present? |

| 24r | 16 | 88 | Anxiety present |

| 24 s | 18 | 100 | Agitation present? |

| 24 t | 14 | 77 | Delirium present? |

| 24u | 13 | 72 | Other psychosocial symptoms present? |

| 25a | 16 | 88 | Was mouth care provided in the last week of life? |

| 25b | 14 | 77 | Was bathing provided in the last week of life? |

| 25c | 16 | 88 | Was incontinence care provided in the last week of life? |

| 25d | 17 | 94 | Was positioning provided in the last week of life? |

| 26 | 17 | 94 | Was the Regional Health End-of-Life Toolkit used? |

| 27a | 18 | 100 | Was a consult made for the Regional Palliative care program? |

| 27b | 18 | 100 | Was a consult made for other MD or NP services? |

| 27c | 18 | 100 | Was a consult made to the site CNS? |

| 27d | 18 | 100 | Was a consult made to the Hospice Palliative care volunteer program? |

| 27e | 18 | 100 | Was a consult made to the Facility Volunteers? |

| 27f | 17 | 94 | Was a consult made to the Speech Language Pathologist? |

| 27 g | 17 | 94 | Was a consult made to the Spiritual Health Practitioner? |

| 27 h | 16 | 88 | Was a consult made to the Registered Dietitian? |

| 27i | 18 | 100 | Was a consult made to the Regional NH CNS? |

| 27j | 14 | 77 | Was a consult made to the Therapeutic Recreation? |

| 27 k | 18 | 100 | Was a consult made to the Respiratory Therapist? |

| 27 l | 18 | 100 | Was a consult made to the Pharmacist? |

| 27 m | 16 | 88 | Was a consult made to Social Work? |

| 27n | 12 | 66 | Was a consult made to the OT/PT/Rehab services? |

| 27o | 18 | 100 | Was a consult made to the manager of food services? |

| 27p | 14 | 77 | Were other consults made? |

| 27q | 18 | 100 | Was a consult made to the Regional ethics committee? |

CNS Clinical Nurse Specialist, NP Nurse Practitioner

Discussion

The ACE instrument, to our knowledge, represents a pioneering effort as the first audit tool specifically developed to assess the multifaceted domains of end-of-life care for nursing home residents, explicitly designed for practical clinical application. Its comprehensive scope and level of detail empower administrators to effectively identify and measure the quality of end-of-life care delivered to residents during their last month of life. The instrument’s development was grounded in an extensive review of the literature on quality care for dying nursing home residents and rigorously validated through a multi-phase process.

The credibility of the ACE instrument is strengthened by its development process, which included face and content validity testing with focus group participants possessing substantial expertise and experience in long-term care. Further validation was achieved through pilot testing, where auditors confirmed the instrument’s ease of use and relatively short completion time. The assessment of inter-rater reliability demonstrated high percentages of agreement between auditors for the majority of items. Discrepancies that did arise often stemmed from the auditors’ need to interpret the intent behind documented notes. For instance, while hydromorphone administration might be documented for “comfort” in a resident’s final days, the underlying reason—whether pain or other undocumented factors—was often unclear. Similarly, notations of “family updates” lacked clarity regarding whether they represented comprehensive end-of-life discussions or simply informational updates. To mitigate these interpretive challenges, enhanced training for future users and the development of a detailed user manual are recommended to guide auditors in consistent and accurate tool application.

While a detailed analysis of specific findings from using the ACE tool is beyond the scope of this paper, several observations made by the auditors warrant discussion. The frequent absence of standardized pain assessment tools in resident charts is concerning, yet aligns with extensive research highlighting inadequacies in pain assessment and management within nursing home settings. Furthermore, the evaluation of intervention effectiveness and pain reassessment are crucial nursing responsibilities, yet limitations in these areas have been noted by multiple researchers. The documentation gaps identified by auditors point to potential weaknesses in nursing documentation practices, a concern echoed by other scholars. This underscores the need for nursing home administrators to reinforce the importance of thorough documentation of care provided to residents and their families. As the well-known adage states, “if it is not documented, it has not been done,” highlighting the critical link between documentation and verifiable care delivery.

Certain limitations of the instrument merit consideration. A degree of subjectivity is inherent in chart audits, although specific steps were taken to minimize this. The ACE tool is designed to record the presence or absence of documented care, rather than evaluate the care’s quality directly. Auditors record whether documentation exists confirming care delivery and provide details about the care, thereby avoiding subjective judgments about care acceptability. However, the interpretation of chart audit reports and judgments regarding care quality will ultimately rest with those who receive and review these reports.

Conclusion

Auditing end-of-life care in nursing homes using tools like the ACE instrument is crucial for driving improvements in care quality. By identifying ineffective practices, informing targeted staff training, and optimizing resource allocation, chart audits can be a catalyst for positive change in clinical practice. This study is significant as it addresses the recognized need for brief, high-quality measures for end-of-life care assessment. Timely data collection is essential for monitoring and enhancing the quality of end-of-life care, requiring valid and reliable data about care processes, recipients, facilities, and caregivers. The development of the ACE chart audit tool, grounded in expert consensus and research literature, provides nursing home facilities with a robust means to monitor and assess the care delivered to residents in their final month of life. These assessments can guide targeted improvements through staff education initiatives, the development of strategies to reduce ineffective practices, and the optimal use of resources. Ultimately, these enhancements will contribute to fostering a culture of care dedicated to delivering the highest quality of end-of-life experiences for every resident.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to research nurses Chloe Shindruk, Paula Black, and Veronika Zot for their dedicated contributions to the research process.

Funding

This project was supported by a grant from the Manitoba Centre for Nursing and Health Research, enabling this important work.

Availability of data and materials

Data from this study are available by contacting the corresponding author, ensuring transparency and access for further research.

Abbreviations

CNS Clinical nurse specialist

NH Nursing home

NP Nurse practitioner

Authors’ contributions

GT served as the principal investigator and project manager, providing overall direction and oversight. The study’s conceptualization was a collaborative effort of all authors. GT coordinated and supervised data collection. Data analysis was conducted by GT and SM. All authors contributed to the review of study findings and participated in drafting and critically revising this paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript, affirming their contributions and agreement with the content.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was formally obtained from the University of Manitoba Education Nursing Research Ethics Board in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada (Reference number E2013:079), ensuring ethical research practices were followed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable as this manuscript does not contain individual person’s data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests, ensuring objectivity and impartiality in this research.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature maintains a neutral stance regarding jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Genevieve N. Thompson, Phone: 204-474-8818, Email: [email protected]

Susan E. McClement, Email: [email protected]

Nina Labun, Email: [email protected].

Kathleen Klaasen, Email: [email protected].

References

[List of original references – to be included here as in the original article]

Associated Data

Data Availability Statement

Please contact the corresponding author for data access.