Background

In the ever-complex landscape of modern healthcare, ensuring continuity of care is paramount. As healthcare systems become more specialized and patients often navigate multiple levels of care, the need to understand and measure the patient experience of this continuity becomes increasingly critical. The Continuity of Care Across Levels from the Patients’ Perspective (CCAENA) questionnaire was developed precisely to address this need. This innovative Continuity Of Care Tool is designed to assess patients’ perceptions of care continuity across different healthcare settings. This article delves into a comprehensive study undertaken to further validate the psychometric properties of the CCAENA questionnaire’s scales, reinforcing its position as a valuable instrument in healthcare research and practice.

Methods

To rigorously evaluate the CCAENA questionnaire, a cross-sectional study was conducted. A random sample of 1500 patients, each having received care in both primary and secondary healthcare settings, was selected from three distinct healthcare areas within the Catalan health system. Data collection was performed in 2010 utilizing the CCAENA questionnaire. The study’s methodology focused on a robust psychometric analysis to ascertain the tool’s effectiveness. Exploratory factor analysis was employed to examine construct validity, ensuring the questionnaire measures the intended concepts. Internal consistency was assessed through item-rest correlations and Cronbach’s alpha, confirming the reliability of the scales. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to investigate multidimensionality, ensuring the distinctiveness of the measured dimensions. Finally, the questionnaire’s ability to differentiate between patient groups based on various characteristics was tested to establish its discriminant validity as a continuity of care tool.

Results

The exploratory factor analysis yielded compelling results, organizing 21 items into three distinct factors. These factors clearly delineated key aspects of patient experience: the patient–primary care provider relationship, the patient–secondary care provider relationship, and crucially, continuity across care levels. The Cronbach’s alpha values for these factors were remarkably high—0.97, 0.93, and 0.80 respectively—indicating excellent internal consistency and reliability of each scale within this continuity of care tool. Furthermore, the calculated correlation coefficients affirmed the multidimensionality of the questionnaire, supporting the interpretation of these dimensions as separate, yet related, scales. Notably, the scales demonstrated the ability to effectively discriminate between patient groups based on healthcare area, age, and educational level, highlighting the tool’s sensitivity to varying patient demographics and contexts.

Conclusion

This rigorous validation study conclusively demonstrates that the CCAENA questionnaire is a valid and reliable continuity of care tool. It effectively measures patients’ perceptions of healthcare continuity across different levels of care. The findings underscore the questionnaire’s potential for practical application by healthcare providers and researchers alike. By utilizing the CCAENA questionnaire, healthcare systems can gain valuable insights into patient experiences, identify specific areas for improvement in care delivery, and ultimately enhance the continuity of care experienced by patients. This tool offers a patient-centered approach to evaluating and improving the coherence and connectedness of healthcare services.

Keywords: continuity of care tool, questionnaires, patient experience, healthcare assessment, healthcare quality, patient-centered care

Introduction

In contemporary healthcare, continuity of care has emerged as a critical focus, driven by the increasing complexity of healthcare delivery, heightened specialization within medical fields, and the involvement of numerous services in patient care pathways. This growing emphasis is further underscored by the rising prevalence of chronic diseases and multimorbidity, where seamless and coordinated care is essential [1, 2]. Drawing upon the conceptual framework established by Reid et al., this article defines continuity of care as “the degree to which patients experience care over time as coherent and linked” [3, 4]. From the patient’s perspective, this experience is a synthesis of several crucial elements: accessible care, effective interpersonal communication, seamless information flow between healthcare professionals and organizations, and robust care coordination to ensure consistent and integrated care delivery [3].

Reid and colleagues further categorized continuity of care into three distinct, yet interconnected, types [3, 4]:

-

Relational Continuity: This dimension reflects patients’ perceptions of an ongoing and therapeutic relationship with one or more healthcare providers. It emphasizes the importance of trust, communication, and a consistent provider-patient interaction over time.

-

Informational Continuity: This aspect focuses on patients’ experiences regarding the availability, utilization, and interpretation of their past medical information to inform and guide current care decisions. Effective information continuity ensures that healthcare providers have access to and utilize relevant patient history to deliver appropriate and personalized care.

-

Managerial Continuity: This dimension pertains to patients’ perceptions of receiving various healthcare services in a coordinated, complementary, and non-duplicative manner. Managerial continuity underscores the importance of seamless transitions between different healthcare services and settings, ensuring a cohesive and integrated care experience.

While relational continuity centers on the ongoing therapeutic relationship between patients and providers, both informational and managerial continuity are fundamentally linked to the perceived interactions and coordination among different healthcare providers involved in a patient’s care journey [3]. Therefore, a comprehensive approach to continuity of care must address all three dimensions to ensure a truly patient-centered and effective healthcare experience.

To effectively monitor and enhance continuity of care, accurate and reliable measurement is indispensable [5]. Assessment should encompass the analysis of relational, informational, and managerial continuity from the patient’s viewpoint, as the patient’s experience is central to the concept of care continuity [3, 6, 7]. A review of existing measurement instruments reveals that many are tailored to specific patient populations [8], such as those with diabetes [9, 10], cancer [11, 12], mental illness [13, 14], or unspecified chronic conditions [15]. Other tools are designed for users in primary care settings or inpatient environments [16, 17].

The CCAENA (Cuestionario Continuidad Asistencial Entre Niveles de AtenciÓn) questionnaire emerged as the first generic tool specifically developed to evaluate continuity of care across different healthcare levels from the perspective of healthcare users, irrespective of their specific morbidity [18]. This continuity of care tool is structured in two sections. The first section focuses on reconstructing the patient’s care trajectory for a particular episode, while the second section, the focus of this study, employs Likert scales to measure patients’ perceptions of the three types of continuity. Since the development of CCAENA, two additional generic tools have been designed to explore patient perceptions of continuity of care: the Nijmegen Continuity Questionnaire [19] and the questionnaire developed by Haggerty et al. [20]. While the CCAENA questionnaire uniquely emphasizes the perceived interaction between providers from different care levels, the other tools also incorporate the perceived interactions among professionals within the same care level. The CCAENA questionnaire’s strength lies in its ability to explore patients’ healthcare journeys across services, pinpointing aspects of healthcare delivery related to continuity of care that are ripe for improvement. Furthermore, it holds the distinction of being the only questionnaire of its kind originally designed in a Spanish-speaking country, making it culturally relevant for Spanish-speaking populations and adaptable for broader international use as a continuity of care tool.

Initial validation of the CCAENA questionnaire indicated its promise as a valuable instrument for assessing continuity of care from the patient’s perspective [18]. The questionnaire demonstrated high face and content validity, adequate comprehensibility, and an acceptable interviewer burden [18]. Moreover, the items exhibited a sound internal structure (construct validity), and the scales achieved acceptable levels of internal consistency. Following this initial testing, refinements were made to the questionnaire, including modifying the item scoring system, ensuring all items were positively formulated, and removing redundant items [18]. Recently, the CCAENA questionnaire was deployed in a large-scale survey of 1500 users to comprehensively analyze patients’ experiences and perceptions of the three dimensions of continuity of care [21, 22]. This article presents a secondary aim of that larger study, which is to provide further robust evidence on the psychometric properties of the CCAENA questionnaire scales, solidifying its standing as a reliable and valid continuity of care tool.

Methods

A cross-sectional study design was implemented, utilizing surveys administered to patients within the Catalonian healthcare system. Three distinct healthcare areas were deliberately selected to capture a range of settings: Baix Empordà (representing a rural and semi-urban mix), the city of Girona (urban), and the Ciutat Vella district of Barcelona (urban). In Baix Empordà, healthcare services across both primary and secondary care levels are provided by a single integrated provider (Serveis de Salut Integrats del Baix Empordà – SSIBE), a public entity operating under private law. Similarly, in Girona, Institut Català de la Salut – ICS, a public entity under public law, serves as the single provider for both primary and secondary care. In contrast, Ciutat Vella presents a more complex service landscape, with primary care delivered by two entities (ICS and Institut de Prestacions d’Assistència Mèdica al Personal Municipal – PAMEM) and secondary care provided by a separate entity (Parc de Salut Mar). The total population aged 18 years and over served by these organizations in the study areas is substantial: 74,144 in Baix Empordà, 83,312 in Girona, and 99,093 in Ciutat Vella [23].

Study Population

The study population comprised patients aged 18 years or older who had received both primary and secondary care within the study areas for the same medical condition within the three months preceding the survey. Exclusion criteria were applied to ensure data quality and relevance: patients who had not been attended to by medical professionals or those who were unable to understand or communicate effectively in either Spanish or Catalan were excluded from participation.

Sample size calculation was meticulously performed to ensure statistical power for multivariate association modeling at a 95% confidence level. The calculation also accounted for the de Moivre theorem, ensuring an expected frequency greater than five, and aimed to facilitate the expression of fit and likelihood statistics as a chi-square distribution. Based on these considerations, the required sample size was estimated to be approximately 400 patients per healthcare area. The final sample size of 1500 patients exceeded this requirement, deemed sufficient for robust analysis of the psychometric properties of the scales within this continuity of care tool [24–26].

A simple random sampling method without replacement was employed to select participants from a comprehensive list of patients who met the inclusion criteria. This list was compiled from records provided by primary care centers and hospitals within the designated healthcare areas. To mitigate potential bias from refusals and ensure the target sample size was achieved, a list of substitutes was also generated, matching individuals by sex and age group to replace any initial non-participants. This rigorous sampling strategy aimed to secure a representative sample and enhance the generalizability of the findings regarding the CCAENA questionnaire as a continuity of care tool.

Measures

The CCAENA questionnaire, at the heart of this study, is specifically designed as a continuity of care tool to comprehensively assess patient-reported experiences of care continuity across different levels of healthcare [18]. The instrument is structured into two distinct sections. The first section is dedicated to reconstructing the patient’s care trajectory for a specific health condition. This section aims to identify key elements of continuity and discontinuity encountered during the transition between primary and secondary care settings. The second section, the primary focus of this psychometric validation, consists of 29 items employing Likert scales. These items are conceptually grouped to measure patients’ perceptions across five key dimensions of continuity of care:

- Patient–Primary Care Provider Relationship (Relational Continuity; 7 items): These items assess the quality and consistency of the relationship between patients and their primary care providers.

- Patient–Secondary Care Provider Relationship (Relational Continuity; 7 items): These items evaluate the relationship between patients and their secondary care providers, mirroring the relational aspect in the secondary care setting.

- Transfer of Medical Information Across Care Levels (Informational Continuity; 4 items): This set of items focuses on patients’ perceptions of how effectively medical information is shared and transferred between primary and secondary care providers.

- Care Coherence Across Care Levels (Managerial Continuity; 7 items): These items explore patients’ experiences of care coordination and coherence as they navigate between primary and secondary care services.

- Accessibility Across Care Levels (Managerial Continuity; 4 items): These items assess patients’ perceptions of the ease and accessibility of care across the different healthcare levels involved in their care.

The response options for the items varied depending on the dimension being measured. For items related to relational continuity, a four-point scale of agreement was used: (1) strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree. For items pertaining to informational and managerial continuity, a frequency-based four-point scale was employed: (2) always, often, occasionally, and never.

To facilitate quantitative analysis, item responses were converted into numerical scores ranging from 0 to 3 points, with higher scores indicating a more positive perception of continuity of care (from strongly disagree/never to strongly agree/always). To address potential missing data, a simple imputation method based on the mean score of the item was applied in cases where fewer than two items were missing per scale and per case. This method is considered appropriate given the high proportion of complete cases within the dataset [27, 28]. Subsequently, item scores within each scale were summed, and this total was then divided by the highest possible score for that scale. Finally, each continuity of care score was transformed into a categorical variable with four levels: very low (≤0.25), low (>0.25 to 0.5), high (>0.5 to 0.75), and very high (>0.75) perception of continuity. This categorization allowed for both continuous and categorical analyses of the continuity of care tool‘s output.

Data Collection

Data collection was primarily conducted through face-to-face interviews with patients, carried out by trained interviewers. The majority of interviews took place at primary care centers (93.7%), with a smaller proportion conducted at patients’ homes (6.1%) and other locations chosen by patients (0.2%). Fieldwork spanned from January to May 2010. This method ensured a high response rate and allowed for clarification and direct engagement with participants during the survey process, enhancing the quality of data collected using the continuity of care tool.

Ethical Considerations

The study was meticulously conducted in full compliance with the ethical research standards stipulated by current European and Spanish legislation [29]. Informed consent was obtained from every participant prior to their inclusion in the survey, ensuring their voluntary participation and understanding of the study’s purpose. Confidentiality of all collected data was rigorously maintained through anonymization during analysis and reporting. The study protocol received formal approval from the Ethical Committee for Clinical Research Parc de Salut Mar (reference number 2009/3414/I), underscoring the ethical rigor of the research process and the responsible use of the continuity of care tool within a validated ethical framework.

Hypothesis

The central hypothesis of this study was that the factor structure of the CCAENA questionnaire scales, as a continuity of care tool, would mirror the established typology of continuity of care defined by Reid et al. [3]. Specifically, it was hypothesized that the questionnaire would effectively differentiate and measure relational continuity, informational continuity, and managerial continuity as distinct yet related constructs. Furthermore, while existing literature presents mixed evidence regarding the association between patient perceptions of continuity of care and organizational or individual patient characteristics [15, 20, 30–34], it was anticipated that the CCAENA scores would demonstrate variability based on the healthcare area in which patients received care. Additionally, it was hypothesized that patient-specific characteristics such as age, educational level, and overall health status might also influence their perceptions of continuity of care as measured by the tool. These hypotheses guided the statistical analyses undertaken to validate the CCAENA questionnaire.

Analyses

Item Analysis

Initial analyses focused on individual item characteristics. Item frequency distributions were examined to understand the response patterns for each item within the continuity of care tool. Rates of missing data were also calculated for each item to identify any potential issues with item comprehension or acceptability. To assess construct validity, exploratory factor analysis was performed. This statistical technique was used to determine whether the items clustered together in a manner consistent with the hypothesized dimensions of continuity of care (structural validity). The number of factors to be retained was determined using two established criteria: visual examination of the scree plot and the Kaiser criterion of eigenvalues greater than 1. Factor analysis was conducted using direct oblimin rotation with Kaiser normalization, an oblique rotation method that accounts for potential correlations between factors, reflecting the likely interconnectedness of different dimensions of continuity of care. Factor loadings, representing the strength of association between each item and its underlying factor, were considered meaningful if they exceeded a threshold of 0.30 or 0.40 [35].

Internal consistency of the scales was evaluated to ensure that items within each scale of the continuity of care tool were measuring the same underlying construct reliably. Item-rest correlations were calculated, representing the correlation between each item and the composite score of the scale formed by all other items. Cronbach’s alpha, a widely used measure of internal consistency reliability, was calculated for each scale. Additionally, Cronbach’s alpha was recalculated for each scale after removing each item in turn (‘Cronbach’s alpha if item deleted’) to assess the impact of individual items on the scale’s overall reliability [36]. A Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.70 or greater was conventionally considered to indicate satisfactory internal consistency for each scale of this continuity of care tool [25].

Scale Score Analysis

Scale score analyses were performed to further evaluate the psychometric properties of the CCAENA questionnaire as a continuity of care tool. To investigate the multidimensionality of the instrument, Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated between the different scales. Spearman’s rho, a non-parametric correlation measure, was used to assess the relationships between the scale scores. Correlation coefficients below 0.70 were interpreted as evidence that the constructed factors could be considered as distinct, separable scales, supporting the multidimensional nature of continuity of care as measured by the CCAENA questionnaire [37].

To assess discriminant validity, Chi-square tests were employed to examine the tool’s ability to differentiate between distinct groups of patients. This analysis tested whether the CCAENA scales could discriminate between patient groups based on the healthcare area where they received treatment and their individual characteristics. Patient characteristics considered included age, educational level, self-rated health status, and the number of clinical conditions reported. For age and educational level, extreme groups were contrasted: younger patients (18–35 years) versus older patients (over 65 years), and patients with no formal education versus those with a university education. Similarly, for the number of clinical conditions, groups were contrasted based on having only one condition versus having more than three conditions. Statistical significance for all analyses was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata statistical package version 11.

Results

Of the patients initially contacted for the study, a substantial proportion (77.5%) declined to participate. However, a comparative analysis was conducted to assess for potential selection bias. This analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between the final sample of participants and the overall study population in terms of key demographic variables, specifically sex and age. Unfortunately, detailed sociodemographic or health characteristic data for the entire study population were not available for more comprehensive comparison.

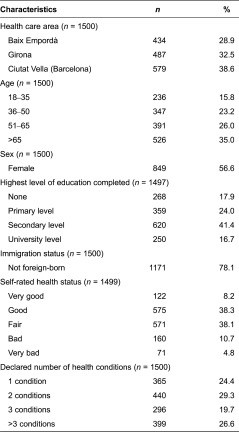

Descriptive statistics of the final sample revealed that over half of the respondents were female (55%), and a majority had attained a primary or secondary level of education (65.4%). A significant proportion (78%) were born in Spain. Regarding self-perceived health status, approximately 57% of patients rated their health as either good or very good. Furthermore, around 24% of the sample reported having only one medical condition (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample

The table “Table 1: Characteristics of the study sample” displays demographic and health-related characteristics of the 1500 participants in the study validating the CCAENA questionnaire, a tool designed to measure continuity of care. It includes categories such as gender (female, male), age groups (18-35, 36-49, 50-64, 65-79, 80+ years), education level (no education, primary, secondary, university), birthplace (Spain, other country), self-rated health status (very good, good, fair, poor, very poor), and number of clinical conditions (1, 2, 3, 4+). For each category, the table presents the frequency (n) and percentage (%) of participants, providing a clear overview of the sample’s composition. This data is crucial for understanding the representativeness of the sample and for interpreting the findings related to the questionnaire’s validity and reliability as a continuity of care assessment tool.

Item Analyses

Analysis of individual items revealed that most items were positively endorsed, with responses skewed towards “agree/totally agree” or “always/often,” particularly for items within the relational continuity scales (Table 2). Missing data rates were generally low across items. However, four items, all conceptually related to care coherence across care levels (items 17–18, 20–21), exhibited non-response rates exceeding 5%. Notably, item 20, specifically concerning the perception of communication among professionals, had a considerably high missing rate of 35.7%. Due to this substantial missing data rate, item 20 was excluded from further scale development and psychometric analysis.

Table 2.

Items response distribution and missing data

The table “Table 2: Items response distribution and missing data” presents a detailed breakdown of responses and missing data for each item of the CCAENA questionnaire. The table is organized by item number and the type of continuity it measures (RC – Relational Continuity, IC – Informational Continuity, MC – Managerial Continuity). For each item, it shows the percentage of responses for each category (e.g., Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Agree, Strongly Agree for Relational Continuity items; Never, Occasionally, Often, Always for Informational and Managerial Continuity items) and the percentage of missing data. This level of detail allows for item-level analysis, revealing response patterns and potential issues such as high missing data rates for specific items. The table is essential for understanding the performance of individual items within the CCAENA questionnaire as a continuity of care tool and for informing decisions about item retention or modification.

IC, informational continuity; MC, managerial continuity; RC, relational continuity.

Construct Validity

To rigorously examine the factor structure of the CCAENA scale, only complete cases, i.e., those where patients responded to all items, were included in the factor analysis (n = 1063). The Kaiser criterion and scree plot analysis both indicated the presence of three dominant factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1 (7.72, 3.59, 1.53) (Table 3). These three factors collectively explained a substantial portion of the variance in item responses, suggesting a meaningful underlying structure within the continuity of care tool.

Table 3.

Factor analysis, item-rest correlation and Cronbach’s alpha of the CCAENA items

The table “Table 3: Factor analysis, item-rest correlation and Cronbach’s alpha of the CCAENA items” presents the results of psychometric analyses conducted on the CCAENA questionnaire. It displays factor loadings from an exploratory factor analysis, item-rest correlations, and Cronbach’s alpha values for each item and scale. Items are grouped according to the three factors identified: Factor I (Patient-Primary Care Provider Relationship), Factor II (Patient-Secondary Care Provider Relationship), and Factor III (Continuity Across Care Levels). For each item, factor loadings on each of the three factors are shown, with loadings exceeding 0.40 highlighted in bold to indicate strong associations. Item-rest correlations and Cronbach’s alpha values (both for the scale with all items and if the specific item is deleted) are also provided, assessing the internal consistency and reliability of the scales. The table includes abbreviations for continuity types (IC, MC, RC) to clarify item categorization. Note ‘a’ indicates response values were reversed for analysis and ‘b’ provides eigenvalues and variance percentages for the three factors. ‘c’ specifies Cronbach’s alpha for the definitive scale of continuity across care levels after item removal. This table provides crucial evidence for the construct validity and reliability of the CCAENA questionnaire as a continuity of care measurement tool.

aResponse values have been reversed for analysis.

bEigenvalues and percentage of variance accounted for by factors I, II and III were 7.725, 3.593 and 1.529, respectively.

cCronbach’s alpha of the definitive scale (items 15–19, 21 and 25) is 0.805.

IC, informational continuity; MC, managerial continuity; RC, relational continuity. Factor loadings that exceded 0.400 are shown in bold.

The factor loading patterns provided further insights into the construct validity of the continuity of care tool. Items conceptually related to relational continuity exhibited strong loadings on the first factor (patient–primary care provider relationship) and the second factor (patient–secondary care provider relationship). The third factor, labeled “continuity across care levels,” was characterized by strong loadings from the four items assessing transfer of information across care levels (items 15–18) and three items related to care coherence across care levels (items 19, 21, and 25). Conversely, items 22–24 and 26–29 did not demonstrate substantial loadings on any of the identified factors and were subsequently excluded from the final scales to enhance the psychometric purity of the continuity of care tool.

Internal Consistency

Evaluation of internal consistency revealed satisfactory results for the refined scales of the continuity of care tool. Item-rest correlations for the selected items were generally robust, exceeding 0.4 for most items. Exceptions were items 19 and 21, which showed slightly lower item-rest correlations (0.360). In contrast, the excluded items consistently exhibited lower item-rest correlations, below 0.3. Cronbach’s alpha values, calculated for each scale, further supported the internal consistency of the instrument. The alpha values were notably high for the patient–primary care provider relationship scale (0.936), the patient–secondary care provider relationship scale (0.931), and the continuity across care levels scale (0.728). Importantly, removing items 22–24 from the continuity across care levels scale resulted in an improved Cronbach’s alpha of 0.805, indicating enhanced internal consistency for the refined scale.

Further analysis explored the internal consistency of two conceptual subscales within the continuity across care levels scale: the transfer of medical information subscale (items 15–18) and the care coherence subscale (items 19, 21, and 25). After removing items 22–24, the Cronbach’s alpha for the transfer of medical information subscale was 0.766, and for the care coherence subscale, it was 0.635. While the latter value is slightly below the conventional 0.70 threshold, it still suggests acceptable internal consistency, particularly for a subscale with fewer items, demonstrating the nuanced psychometric properties of this continuity of care tool.

Scale Score Analysis

Based on the factor analysis and internal consistency results, three primary scales were constructed for the continuity of care tool:

- Patient–Primary Care Provider Relationship – Relational Continuity (items 1–7)

- Patient–Secondary Care Provider Relationship – Relational Continuity (items 8–14)

- Continuity Across Care Levels – Informational and Managerial Continuity (items 15–19, 21, and 25)

Additionally, two subscales were derived from the continuity across care levels scale for more granular analysis:

- Transfer of Medical Information Across Care Levels Subscale (items 15–18)

- Care Coherence Across Care Levels Subscale (items 19, 21, and 25)

Multidimensionality

Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the interrelationships between these scales and subscales, providing evidence for the multidimensionality of the continuity of care tool. The correlation coefficients between all pairs of scales were below the 0.70 threshold (Table 4). This finding supports the interpretation that these scales represent distinct, albeit related, dimensions of continuity of care. Specifically, the correlation between the ‘transfer of medical information across care levels’ subscale and the ‘care coherence across care levels’ subscale was 0.511, indicating that while these subscales are related, they measure sufficiently distinct aspects of continuity to be considered as separate scores within the broader continuity of care tool.

Table 4.

Spearman correlation coefficients between scalesa

IC, informational continuity; MC, managerial continuity; PC, primary care; RC, relational continuity; SC, secondary care.

aSpearman correlation coefficients calculated using definitive scales.

Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity analyses examined the ability of the CCAENA scales to differentiate between patient groups based on relevant characteristics. Table 5 presents the percentage of patients within each subgroup who perceived high or very high continuity of care for each scale, along with the statistical significance (p-value) of differences in scores between selected subgroups. The results demonstrated that the scales effectively discriminated between patients based on the healthcare area where they received care, age group, and level of education. For instance, a notable difference was observed in the perception of continuity across care levels between younger and older patients. Specifically, 58.9% of patients aged 18–35 years reported high or very high levels of continuity across care levels, whereas this percentage significantly increased to 89.3% among patients older than 65 years.

Table 5.

Differences in scores between subgroups

aPercentage of patients perceiving high or very high continuity of care.

bP-value associated for Chi-square test comparing very high, high, low and very low perceptions of continuity of care among groups.

IC, informational continuity; MC, managerial continuity; PC, primary care; RC, relational continuity; SC, secondary care.

Interestingly, only the scale measuring continuity across care levels and its subscale focusing on the transfer of medical information across care levels demonstrated the ability to discriminate between patients based on their self-rated health status and the number of clinical conditions they reported. The relational continuity scales (patient–primary care provider relationship and patient–secondary care provider relationship) did not show significant discrimination based on these health-related patient characteristics. These findings offer nuanced insights into the differential sensitivity of various dimensions of continuity of care as measured by the CCAENA questionnaire.

Discussion

The CCAENA© questionnaire is a generic continuity of care tool designed with a dual purpose: first, to explore patients’ healthcare trajectories and identify elements of (dis)continuity during transitions between care levels [21], and second, to quantify patients’ perceived degree of continuity of care using Likert scales [22]. Prior to this study, the questionnaire underwent initial validation involving expert review, two pretests, and a pilot test with 200 healthcare users [18]. The results presented in this article represent an extended and more robust validation of the CCAENA questionnaire scales, solidifying its psychometric properties as a reliable continuity of care tool. Two primary hypotheses, concerning the psychometric characteristics and discriminant validity of the CCAENA questionnaire, were rigorously tested in a large and diverse sample of patients. This sample encompassed individuals from various age groups, with diverse medical conditions, and receiving care in different settings within the Catalan healthcare system, enhancing the generalizability of the validation findings for this continuity of care tool.

The first hypothesis, positing that the factor structure of the CCAENA scales would align with Reid et al.’s typology of continuity of care [3], was partially supported by the factor analysis results. The analysis identified two factors representing relational continuity (patient–primary and secondary care provider relationship) and a third factor capturing the perception of continuity across care levels (encompassing both transfer of medical information and care coherence across care levels). These scales also demonstrated satisfactory levels of internal consistency, and the multidimensionality of the scales was substantiated by the inter-factor correlation analyses. The finding that items related to informational and managerial continuity loaded onto a single factor, ‘continuity across care levels,’ is theoretically consistent with recent studies suggesting that patients primarily differentiate between relational continuity and a broader concept of ‘seamless care,’ which integrates aspects of both informational and managerial continuity [5, 38]. Interestingly, the validation process of the Nijmegen Continuity Questionnaire also observed a similar structural distribution of items [19], further supporting this conceptual grouping. In addition, this study explored the psychometric properties of the two conceptual subscales within the ‘continuity across care levels’ scale: ‘transfer of medical information across care levels’ and ‘care coherence across care levels.’ This subdivision is grounded in the conceptual framework guiding the study [3] and is further supported by reliability and multidimensionality analyses, which demonstrate adequate internal consistency for each subscale and sufficient uncorrelatedness to warrant their consideration as separate scores within this continuity of care tool.

The second hypothesis, anticipating that the CCAENA scores would effectively differentiate perceptions between patient groups, was also partially supported by the discriminant analyses. The scales successfully discriminated patients based on the healthcare area they were attended to and certain individual characteristics, specifically age and education level. However, only the ‘continuity across care levels’ scale and its ‘transfer of medical information across care levels’ subscale were able to differentiate patients based on their self-rated health status. The mixed evidence in existing literature regarding the link between continuity of care and morbidity [15, 30, 34] suggests two possible interpretations for this finding. First, it is possible that genuine differences in relational and care coherence perceptions related to health status exist, but the CCAENA scales, as a continuity of care tool, may lack sufficient discriminant ability to detect these subtle differences. Alternatively, it is also plausible that perceptions of these types of continuity genuinely do not vary significantly according to health status, as suggested by some prior research [15, 30]. Further research is warranted to explore this issue in more depth and refine the understanding of the relationship between patient health status and perceived continuity of care.

The psychometric evaluation process indicated that removing four items related to care coherence and four items related to accessibility across care levels could potentially enhance the scales’ psychometric properties. However, it was decided to retain these items in the questionnaire due to their conceptual relevance and importance in comprehensively understanding patients’ perceptions of continuity of care. The structural behavior of items related to care coherence may be attributed to the multifaceted nature of this construct, which encompasses several attributes that are not necessarily strongly inter-correlated, as previously observed [18]. These attributes include perceptions of care coordination, communication between services, avoidance of duplicate tests, appropriate sequencing of care, and adequate patient follow-up. Similarly, the limited internal consistency of items related to accessibility across care levels might stem from the fact that accessibility to primary care and accessibility to secondary care are distinct aspects that may not be strongly correlated. While splitting this scale into two separate scales (items 26 and 29; items 27–28) was considered, it was ultimately rejected due to the general recommendation in psychometric literature that scales should ideally comprise at least three items [39].

In conclusion, this validation research aligns with the findings of the initial validation process [18] and provides further robust evidence that the CCAENA questionnaire is a valid and reliable continuity of care tool for measuring patients’ perceptions of continuity of care. Healthcare providers and researchers seeking to improve continuity of care across different healthcare levels can confidently apply the CCAENA questionnaire to identify specific areas for targeted improvement and to monitor the impact of interventions aimed at enhancing patient-centered, coordinated care.

Contributor Information

Marta-Beatriz Aller, Health Policy and Health Services Research Group, Health Policy Research Unit. Consortium for Health Care and Social Services of Catalonia, Barcelona, Spain.

Ingrid Vargas, Health Policy and Health Services Research Group, Health Policy Research Unit, Consortium for Health Care and Social Services of Catalonia, Barcelona, Spain.

Irene Garcia-Subirats, Health Policy and Health Services Research Group, Health Policy Research Unit, Consortium for Health Care and Social Services of Catalonia, Barcelona, Spain.

Jordi Coderch, Grup de Recerca en Serveis Sanitaris i Resultats en Salut (GRESSIRES), Serveis de Salut Integrats Baix Empordà, PalamÓs, Spain.

Lluís Colomés, Health Policy and Health Services Research Group; Strategic Planning Division, SAGESSA Group, Reus, Spain.

Josep Ramon Llopart, Health Policy and Health Services Research Group; Division of Management, Planning and Organizational Development, Badalona Healthcare Services (BSA), Badalona, Spain.

Manel Ferran, Teaching Department, Catalan Health Institute (ICS), Barcelona, Spain.

Inma Sánchez-Pérez, Grup de Recerca en Serveis Sanitaris i Resultats en Salut (GRESSIRES), Serveis de Salut Integrats Baix, PalamÓs, Spain.

M. Luisa Vázquez, Health Policy and Health Services Research Group, Health Policy Research Unit, Consortium for Health Care and Social Services of Catalonia, Barcelona, Spain.

Funding

This work was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the European Regional Development Fund (Fondos FEDER) [PI08/90154], which partially financed the study.

Reviewers

Silvina Berra, MPH, PhD, Professor and Researcher, School of Public Health, National University of Cordoba, Argentina

Montserrat Ferrer, PhD, Senior Researcher at the Health Services Research Group, IMIM (Institut Hospital del Mar d′Investigacions Mediques), Barcelona, Spain

References

[1] Starfield B. Primary care. Is it essential? Lancet. 1994;344(8930):1129–33. [PubMed]

[2] Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1996;74(4):511–44. [PubMed]

[3] Reid RJ, Haggerty JL, McKendry R,