Introduction

By 2040, projections indicate that a significant majority, around 87.6%, of individuals in England and Wales who pass away will require palliative care [1]. During their final stages of life, individuals may face distressing symptoms such as pain, breathing difficulties, and confusion [2]. To evaluate the effectiveness of care provided at the end of life, and to understand the quality of the dying process and death itself, numerous assessment tools have been developed [3–7]. However, effectively measuring the quality of dying, death, and end-of-life care presents unique challenges. These include the deteriorating health of individuals nearing death, the complexity of identifying those in the terminal phase, and the delicate nature of involving bereaved families in quality assessments during such a sensitive period. Furthermore, the creation and validation of new Death Care Tools are resource-intensive and time-consuming. Consequently, focusing on the evaluation and enhancement of existing tools might be a more productive approach than continuously developing new ones.

Tools designed to assess the quality of end-of-life care often concentrate on the practical aspects of care delivery. These instruments frequently include items evaluating the care environment, the effectiveness of communication with healthcare and social care professionals, and the standard of nursing care. Conversely, death care tools specifically aimed at evaluating the quality of dying and death delve into the broader spectrum of patient needs. These tools consider physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual well-being, the burden of symptoms experienced, and the location of death. Several systematic reviews have explored the application of these tools across diverse patient populations, including those with dementia and cancer [3–7]. Notably, recent research has differentiated between tools assessing the quality of dying and death and those evaluating care quality within long-term care settings [7]. Similarly, van Soest-Poortvliet et al. [6] adopted a structured methodology to evaluate the psychometric properties of tools designed to capture both end-of-life care quality and the quality of dying in long-term care environments, also examining potential variations for individuals with and without dementia. However, their psychometric property assessments relied on data collected in the USA and the Netherlands. The current review adopts a broader perspective. It evaluates the psychometric properties of all death care tools developed and validated to assess, retrospectively, the quality of dying and death and the quality of end-of-life care across various care settings, alongside the methodological rigor of studies reporting these properties. While acknowledging the potential for recall bias in retrospective assessments, this approach circumvents the challenge of definitively determining whether a patient was in the terminal phase at the time of assessment.

This review employs the COSMIN (Consensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments) framework [8], a recognized taxonomy designed to standardize the terminology and definitions of psychometric properties [9], and to offer guidelines on optimal methods for tool development and validation [10]. Since its inception, COSMIN [8] has been utilized to evaluate tools developed for various clinical populations, including dementia [11, 12] and breast cancer [13], as well as tools assessing quality of life in palliative care settings [14] and the quality of care and dying in long-term care environments [6].

Aims

This systematic review aimed to:

- Identify all death care tools used post-mortem to assess the quality of death and dying, and the quality of end-of-life care.

- Evaluate the psychometric properties of these death care tools.

- Provide recommendations for validated death care tools suitable for use in research and clinical practice.

Method

The protocol for this review is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42016047296) and adheres to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [15]. The PRISMA checklist is available in Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) 1.

Search Strategy

We conducted searches in the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO databases from their inception up to May 15, 2017. Search terms included medical subject heading (MeSH) terms relevant to death care tools, end of life, quality of death and dying, and quality of care (Box 1). Terms related to the end-of-life care population were derived from a previous Cochrane review [16]. We also manually reviewed the reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews to identify any additional pertinent studies.

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (1) studies that assessed at least one psychometric property of a tool evaluating the quality of death and dying and/or end-of-life care for adult palliative care patients in inpatient or community settings; (2) tools completed post-mortem by family members and healthcare professionals (HCPs) of deceased patients; (3) studies reported in English, even if the psychometric properties of the tool were developed and validated in another language; and (4) studies published in peer-reviewed journals. Exclusion criteria included studies reporting on (1) ad hoc tools, (2) single-item tools, (3) tools developed solely for study purposes, and (4) tools designed for critical care settings (e.g., intensive care units). Since COSMIN is designed to assess the methodological quality of studies using classical test theory or item response theory (IRT), we excluded studies using other methodologies like generalizability theory [17]. Assessment tools like the Mini-Suffering State Examination (MSSE) [18] and Palliative Outcome Scale (POS) [19] were excluded because MSSE assesses diverse symptoms not intended to correlate and thus not reflective of an overall construct. POS has been shown to capture two factors and some independent items [20], making it less suitable for assessing internal consistency and factor structure.

Study Selection

The study selection process was conducted in two phases. Initially, all citations were reviewed, followed by a full-text review of studies meeting the initial inclusion criteria. One researcher (NK) screened all titles and abstracts. Three reviewers (BV, JH, TA) independently assessed a random sample of 250 abstracts and titles each (750 total). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. This process ensured clarity and agreement on the appropriateness and detail of the inclusion criteria. One researcher (NK) screened all full-text studies, consulting with a second reviewer (TA) when study relevance was unclear. Study authors were contacted for clarification if needed.

Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers (NK in all cases, plus one of TA, GTR, GS, NW, SH, and TF) using a standardized form. Extracted data included: country of origin, study aim, tool(s) developed and/or validated, tool aim(s), number of items, response scale, language of tool assessed, respondent type (family or HCP), recall period, administration method, study setting, patient population, sample size, and demographic information of respondents and/or deceased patients.

Assessment of Psychometric Properties

Psychometric properties of the death care tools were evaluated using established quality criteria [21, 22; Table 1]. COSMIN guidelines were used to assess various properties, including validity (content, construct [structural, hypothesis testing, and cross-cultural], and criterion), reliability (internal consistency, reproducibility [agreement and reliability over time and between/within raters], responsiveness, and floor/ceiling effects). Criterion validity was not assessed as no ‘gold standard’ tool exists for measuring end-of-life care quality and dying quality. Each property was scored as positive (+), indeterminate (?), negative (−), or no information (0) based on criteria in Table 1.

Table 1.

Quality criteria used to assess psychometric properties of measures [22]

| Psychometric property | Definition | Rating | Quality criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal consistency | Extent of item correlation, indicating overall tool measures same construct | + | Adequate sample data for factor analysis; Cronbach’s α per factor between 0.70 and 0.95 |

| ? | No factor analysis conducted | ||

| − | Cronbach’s α > 0.95 | ||

| Reliability | Degree to which scores are free from measurement error | + | ICC or weighted kappa ≥ 0.70 |

| ? | ICC or weighted kappa not reported or inappropriate statistical method | ||

| − | ICC or weighted kappa < 0.70 | ||

| Content validity | Extent items reflect construct being assessed | + | Detailed description of tool development, including aim, target population, concepts, item selection, and population (patient & experts) involved |

| ? | Aspects of tool development lack description or only target population involved | ||

| − | No target population involved | ||

| Structural validity | Degree to which tool scores reflect construct dimensions | + | Factor analysis shows combined factors explain ≥ 50% variance OR IRT confirms (uni) dimensionality |

| ? | Proportion of variance explained not reported | ||

| − | Factor analysis does not confirm structure | ||

| Hypothesis testing | Extent tool scores align with pre-formulated hypotheses | + | Specific hypotheses formulated; ≥ 75% results align with hypotheses |

| ? | No a priori formulated hypotheses | ||

| − | Results contradict hypotheses | ||

| Cross-cultural validity | Adequacy of translated version reflecting original | Assessed using methodological quality criteria only | |

| Item response theory | Assesses item responses related to unmeasured ‘trait’ | Assessed using methodological quality criteria only |

Psychometric property ratings: + indicates positive; ? indicates indeterminate; − indicates negative

ICC Intraclass correlation coefficient, IRT item response theory

Assessment of Methodological Quality

The methodological quality of studies reporting psychometric properties of death care tools was appraised using the COSMIN checklist [21]. This checklist includes nine boxes, each rating a specific psychometric property on 5–18 items as excellent, good, fair, or poor. Methodological and psychometric quality were assessed for all properties except cross-cultural validity and IRT, which were rated only on methodological quality. Assessments were based on the overall tool when possible; subscales were assessed individually if studies reported properties for subscales rather than the whole tool. Two independent reviewers (NK, plus one of TA, GTR, GS, NW, SH, and TF) assessed each study. Ratings were compared, discrepancies discussed and resolved, with a third rater consulted if needed. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) between reviewers for methodological quality assessment ranged from 0.70 to 0.97, and high agreement was found for psychometric property appraisal (ICC range 0.87–1.0).

Levels of Evidence

For each psychometric property assessed, the level of evidence supporting the rating was determined. This was based on the number of studies, methodological quality (COSMIN), and consistency across studies. Levels were rated as strong (consistent findings across several ‘good’ studies or one ‘excellent’ study), moderate (consistent evidence across several ‘fair’ studies or one ‘good’ study), limited (findings from one ‘fair’ study), unknown (findings from ‘poor’ studies), or conflicting (inconsistent findings across studies) [23].

Data Synthesis

Rating data for the same tools from different studies were grouped by methodology. Grouping was possible for studies using the same tool version (items, scale, language) and respondent type (family/HCP). For tools where grouping was not possible, ratings were presented individually. Where grouping was possible, only data from studies rated as fair, good, or excellent on methodological quality (COSMIN [21]) were used.

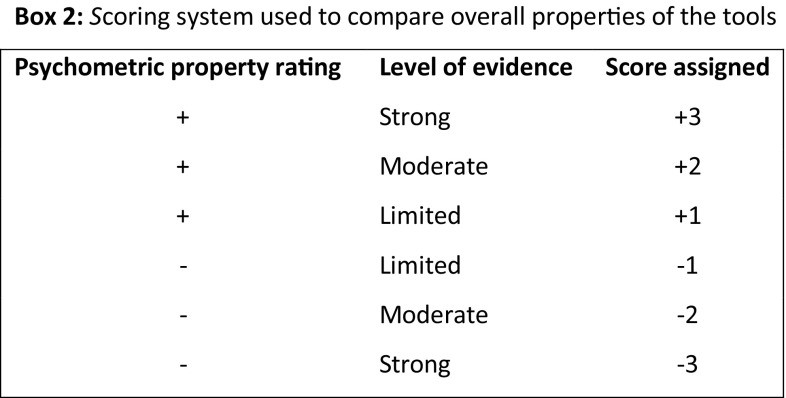

To compare tools globally, an ad hoc scoring system was developed, assigning scores for psychometric property ratings and evidence levels (Box 2).

Psychometric properties rated indeterminate (?), unknown, or conflicting received a score of 0. Scores for each property were summed for an overall tool score.

Results

Search Results and Study Selection

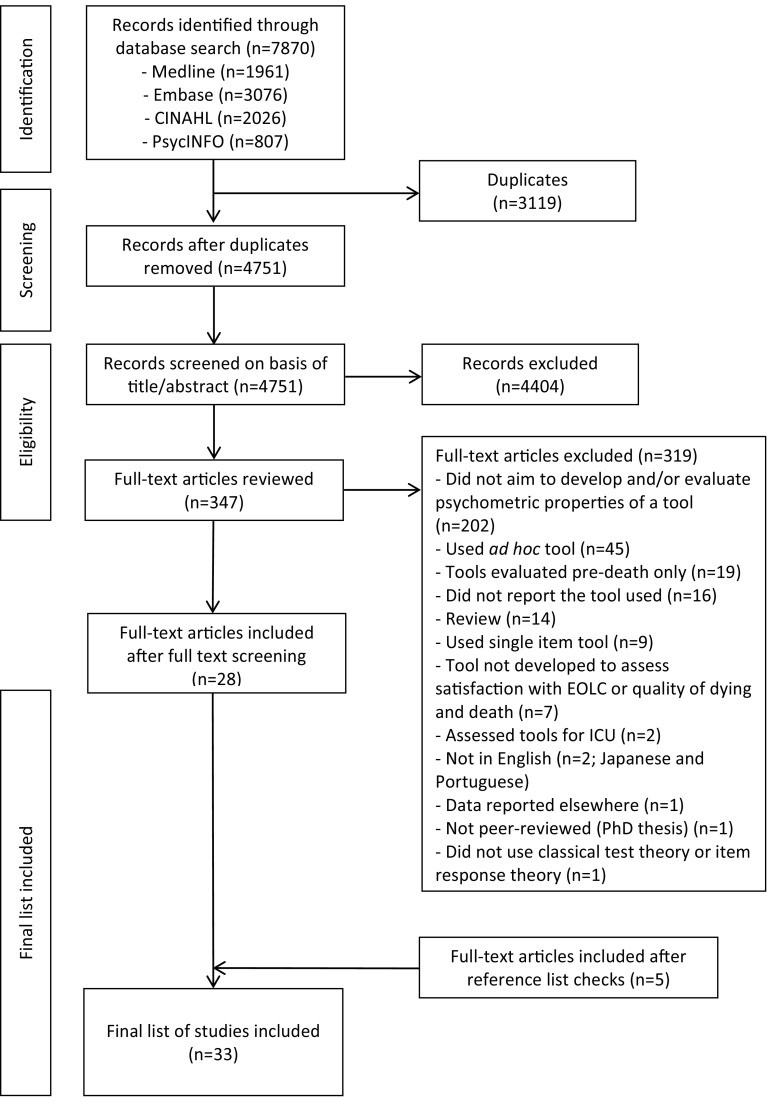

Database searches yielded 4751 studies. After abstract and title screening, 347 studies underwent full-text review, with 28 meeting inclusion criteria. Reference checks of these 28 studies identified five additional relevant studies, resulting in a final set of 33 studies for review. A PRISMA flow diagram of the screening process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram of study selection. EOLC end-of-life care, ICU intensive care unit

The 33 studies assessed 67 death care tools. Most studies assessed tools completed by family carers (n = 57), some by HCPs (n = 8), or both (n = 2). Tools were in English (n = 44), Dutch (n = 11), German (n = 2), Japanese (n = 4), Korean (n = 2), Spanish (n = 2), and Italian (n = 1). One study used both English and Spanish versions. Studies were from the USA (n = 14), Japan (n = 4), UK (n = 3), Netherlands (n = 3), Korea (n = 2), and Germany (n = 2). One study was international (Canada, Chile, Ireland, Italy, Norway). Studies evaluated care and dying quality in palliative care units (n = 10), long-term care settings including nursing homes (n = 7), hospitals (n = 2), hospices (n = 1), home (n = 1), outpatient units (n = 1), and across various settings (n = 9). Clinical populations were mixed (n = 15), advanced cancer (n = 14), or advanced dementia (n = 4).

All but one study [7] evaluated psychometric properties of overall tools and/or subscales, except for the Minimum Data Set (MDS), evaluated as individual subscales. ESM 2 summarizes included studies. Family carer and HCP tools, translated versions, and subscales were evaluated individually, totaling 67 tool assessments. Of these, 35 assessed care quality, 22 dying and death quality, and 10 both. Most studies assessed one tool version with a single sample (n = 21), some assessed two (n = 8), three (n = 1), four (n = 1), 11 (n = 1), or 12 (n = 1) individual tools differing in evaluation focus or respondent type. ESM 3 summarizes all tools per study.

Psychometric Properties of Tools

Data on psychometric properties could not be grouped for all death care tools due to significant study differences in tool versions (original, abbreviated, language), usage methods (family/HCP, self-administered/interview), and settings (long-term care, hospice, hospital). Ratings for tools from ungrouped studies are presented individually; grouped studies used similar tools and methods. Table 2 summarizes psychometric property ratings, evidence levels, and overall scores for each tool. ESM 4 details psychometric property appraisals and methodological quality using the COSMIN checklist.

Table 2.

Data synthesis of quality of psychometric properties and level of evidence for tools

| Tool (respondent) | Studies (n) | Internal consistency | Reliability | Content validity | Structural validity | Hypotheses testing | Cross-cultural | IRT | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PQ | LOE | PQ | LOE | PQ | LOE | PQ | LOE | PQ | LOE |

| Quality of care | |||||||||

| CODE (FC) [31] | 1 | + | Moderate | Unknown | + | Strong | ? | Moderate | ? |

| SWC-EOLD (FC) [7, 24] | 2 | + | Strong | Unknown | ? | Strong | ? | Moderate | 3 |

| FATE-32 (FC) [29] | 1 | + | Limited | + | Limited | ? | Limited | ? | Limited |

| CQ-Index-PC2 (FC) [33] | 1 | ? | Limited | + | Moderate | ? | Limited | 2 | |

| QPM-SF3 (FC) [34] | 1 | − | Limited | − | Limited | + | Strong | + | Limited |

| FAMCARE-10 (FC) [30] | 1 | + | Limited | + | Limited | Moderate | 2 | ||

| FAMCARE-5 (FC) [30] | 1 | + | Limited | + | Limited | Moderate | 2 | ||

| FPCS (FC) [7, 25] | 2 | − | Limited | + | Moderate | + | Limited | ? | Moderate |

| TIME (FC) [7, 26] | 2 | + | Moderate | Unknown | ? | Moderate | ? | Moderate | 2 |

| SAT-Fam-IPC (FC) [35] | 1 | − | Moderate | + | Moderate | + | Moderate | Unknown | Unknown |

| CES-104 (FC) [32] | 1 | Unknown | + | Moderate | 2 | ||||

| FPPFC (FC) [7] | 1 | + | Moderate | ? | Moderate | ? | Limited | 2 | |

| FAMCARE (FC) [37] | 1 | − | Moderate | + | Strong | Moderate | 1 | ||

| ECHO-D (FC) [27, 28] | 2 | + | Limited | − | Limited | Unknown | + | Limited | 1 |

| MDS-Mood (FC) [7] | 1 | + | Limited | ? | Moderate | ? | Limited | 1 | |

| FATE-S-141 (FC) [38] | 1 | Unknown | ? | Limited | Unknown | 0 | |||

| FATE-S-12 (FC) [7] | 1 | Unknown | ? | Limited | 0 | ||||

| FATE-S-122 (FC) [39] | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | 0 | |||||

| SWC-EOLD2 (FC) [39] | 1 | ? | Limited | 0 | |||||

| FPCS2 (FC) [39] | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 0 | ||||

| TIME2 (FC) [39] | 1 | Unknown | ? | Limited | Unknown | 0 | |||

| McCusker EOLC scale (FC) [54] | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | 0 | |||||

| CES (FC) [36] | 1 | − | Limited | − | Limited | + | Moderate | ? | Limited |

| CES4 (FC) [32] | 1 | − | Moderate | + | Moderate | ? | Moderate | ? | Limited |

| FPPFC2 (FC) [39] | 1 | Unknown | ? | Limited | Unknown | 0 | |||

| MDS-Spirituality (FC) [7] | 1 | Unknown | ? | Limited | 0 | ||||

| MDS-Social (FC) [7] | 1 | − | Limited | ? | Moderate | ? | Limited | − 1 | |

| MDS-Symptoms (FC) [7] | 1 | − | Moderate | ? | Moderate | ? | Limited | − 2 | |

| CES5 (FC) [40] | 1 | − | Strong | ? | Strong | Unknown | Limited | − 3 | |

| CEQUEL (FC) [41] | 1 | − | Strong | ? | Strong | ? | Limited | − 3 | |

| Quality of dying and death | |||||||||

| SPELE (HCPs) [47] | 1 | Unknown | + | Moderate | 2 | ||||

| QODD (FC) [42, 43] | 2a | Unknown | ? | Strong | + | Limited | 1 | ||

| CAD-EOLD (FC) [7, 24] | 2 | Conflicting | Unknown | Conflicting | ? | Moderate | 0 | ||

| CAD-EOLD2 (FC) [39] | 1 | ? | Limited | Unknown | ? | Limited | 0 | ||

| CAD-EOLD (HCPs) [55] | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | ? | Limited | 0 | |||

| SM-EOLD (FC) [7, 24] | 2 | Conflicting | Unknown | Conflicting | ? | Moderate | 0 | ||

| SM-EOLD2 (FC) [39] | 1 | Unknown | ? | Limited | 0 | ||||

| SM-EOLD2 (HCPs) [39] | 1 | Unknown | ? | Limited | 0 | ||||

| SM-EOLD (HCPs) [56] | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | 0 | |||||

| MSAS-GDI (FC) [57] | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | 0 | |||||

| QODD-ESP7 (FC) [46] | 1 | ? | Moderate | Limited | 0 | ||||

| QODD-ESP-127 (FC) [46] | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | 0 | |||||

| CAD-EOLD2 (HCPs) [39] | 1 | − | Limited | Unknown | ? | Limited | ? | Limited | − 1 |

| QODD-D-Ang6 (FC) [44] | 1 | Unknown | ? | Limited | Unknown | − | Strong | ? | Limited |

| QODD-D-MA6 (HCPs) [45] | 1 | Unknown | ? | Limited | − | Strong | Unknown | Unknown | − 3 |

| Quality of care and dying and death | |||||||||

| QOD-LTC-C (FC and HCPs) [48] | 1 | + | Strong | Unknown | ? | Strong | 3 | ||

| GDI5 (FC) [49] | 1 | + | Strong | ? | Strong | Unknown | Limited | 3 | |

| GDI-Short version4 (FC) [51] | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | 0 | |||||

| QOD-Hospice Short Form (FC) [50] | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 0 | ||

| QOD-LTC (FC) [7] | 1 | Unknown | ? | Moderate | 0 | ||||

| QOD-LTC2 (FC) [39] | 1 | ? | Limited | Unknown | ? | Limited | Unknown | 0 | |

| QOD-LTC2 (HCPs) [39] | 1 | − | Limited | Unknown | ? | Limited | ? | Limited | Unknown |

| QOD-Hospice (FC) [50] | 1 | Unknown | − | Limited | Unknown | Unknown | − | Limited | − 2 |

| GDI4 (FC) [51] | 1 | Unknown | − | Moderate | ? | Limited | ? | Limited | − 2 |

| QOD-LTC (FC and HCPs) [48] | 1 | − | Strong | − | Moderate | Unknown | − | Strong | − 8 |

Psychometric property quality ratings: + indicates positive, ? indicates indeterminate, − indicates negative

Level of evidence: strong = consistent findings across several studies with a methodological rating of ‘good’ or one study rated as ‘excellent’; moderate = consistent evidence across several studies rated as ‘fair’ or one study rated as ‘good’ in methodological quality; limited = findings from one study rated as ‘fair’; unknown = findings from studies rated as ‘poor’ available; conflicting = inconsistent findings across different studies

Tool completed in: 1 = English and Spanish; 2 = Dutch; 3 = Italian; 4 = Japanese; 5 = Korean; 6 = German; 7 = Spanish

CAD–EOLD Comfort Assessment in Dying at the End of Life in Dementia, CEQUEL Caregiver Evaluation of the Quality of End of Life care, CES Care Evaluation Scale, CODE Caring Of the Dying Evaluation, CQ–Index–PC Consumer Quality Index Palliative Care, ECHO–D Evaluating Care and Health Outcomes-for the Dying, EOLC end-of-life care, FAMCARE Family satisfaction with end-of-life Care, FATE Family Assessment of Treatment at the End of life, FC family carers, FPCS Family Perceptions of Care Scale, FPPFC Family Perceptions of Physician-Family Caregiver Communication, GDI Good Death Inventory, HCPs healthcare professionals, IRT item response theory, LOE level of evidence, MDS minimum data set, MSAS–GDI Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale Global Distress Index, PQ psychometric quality, QODD Quality of Dying and Death, QODD–D–Ang QODD-Deutsch-Angehörige, QODD–D–MA QODD-Deutsch-Mitarbeiter, QODD–Esp Spanish version of the QODD, QOD–Hospice Quality Of Dying-Hospice scale, QOD–LTC Quality Of Dying in Long-Term Care, QOD–LTC–C Quality Of Dying in Long-Term Care of Cognitively intact decedents, QPM–SF Post Mortem Questionnaire-Short Form, SAT–Fam–IPC Satisfaction Scale for Family members receiving Inpatient Palliative Care, SM–EOLD Symptom Management at the End of Life in Dementia, SPELE Staff Perception of End of Life Experience, SWC–EOLD Satisfaction With Care at the End of Life in Dementia, TIME Toolkit of Instruments to Measure End of life care after-death bereaved family member interview

aStudy 46 assessed the QODD in two separate family carer samples

Psychometric Properties of Tools Assessing Quality of Care at the End of Life

Table 2 presents death care tools identified for assessing end-of-life care quality. Data were grouped for SWC-EOLD (Satisfaction With Care at the End of Life in Dementia) [7, 24], FPCS (Family Perceptions of Care Scale) [7, 25], TIME (Toolkit of Instruments to Measure End of life care after-death bereaved family member interview) [7, 26], and ECHO-D (Evaluating Care and Health Outcomes-for the Dying) [27, 28]. Internal consistency, structural validity, and hypothesis testing were assessed for all four, while content validity was evaluated for SWC-EOLD [7, 24] and FPCS [7, 25], and reliability for TIME [7, 26] and ECHO-D [27, 28]. SWC-EOLD [7, 24] showed strong positive internal consistency (Cronbach’s α 0.83–0.90), moderate-to-strong indeterminate structural validity and hypothesis testing evidence, and unknown content validity (indeterminate rating from a poor-quality study). FPCS [7, 25] showed limited negative internal consistency (α = 0.95 and 0.96), positive content and structural validity, and indeterminate hypothesis testing. TIME [7, 26] had moderate positive internal consistency (α = 0.94), indeterminate structural validity and hypothesis testing, and unknown reliability. ECHO-D [27, 28] showed limited positive internal consistency (α = 0.78–0.93) for subscales, suitability for hypothesis testing, but negative test–retest reliability (kappa [κ] < 0.40).

For ungrouped death care tools, FATE (Family Assessment of Treatment at the End of life)-32 [29], FAMCARE (Family satisfaction with end-of-life Care)-5 and -10 [30], CODE (Caring Of the Dying Evaluation) [31], FPPFC (Family Perceptions of Physician-Family Caregiver Communication) [7], and MDS-Mood [7] had positive internal consistency (α = 0.74–0.94) with varying evidence levels. Japanese CES (Care Evaluation Scale) and CES-10 [32] versions showed moderate positive test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.82–0.83). FATE-32 [29], CQ-Index-PC (Consumer Quality Index Palliative Care) [33], QPM-SF (Post Mortem Questionnaire-Short Form) [34], SAT-Fam-IPC (Satisfaction Scale for Family members receiving Inpatient Palliative Care) [35], CES [36], and CODE [31] had strong-to-moderate positive content validity, with strong evidence for QPM-SF [34] and CODE [31]. QPM-SF [34], FAMCARE [37], FAMCARE-5 and FAMCARE-10 [30], and SAT-Fam-IPC [35] showed positive structural validity, with strong evidence for FAMCARE [37]. Cross-cultural validity was assessed for FATE-S-14 [38], Dutch FATE-S-12, FPCS, TIME, and FPPFC [39], SAT-Fam-IPC [35], and Korean/English CES [36, 40]. Methodological quality was poor for all but Korean CES [40] (fair), thus cross-cultural validity is mostly unknown (limited for Korean CES [40]). IRT methodology was used for FAMCARE scales (FAMCARE [37], FAMCARE-10, FAMCARE-5 [30]), rated as good with moderate evidence.

Using the ad hoc scoring system, 15 of 30 death care tools scored positively. CODE [31] and SWC-EOLD [7, 24] scored ≥ + 3, while MDS-Social [7], MDS-Symptoms [7], Korean CES [40], and CEQUEL (Caregiver Evaluation of the Quality of End of Life care) [41] scored poorly (− 1 to − 3).

Psychometric Properties of Tools Assessing Quality of Dying and Death

Table 2 shows death care tools assessing dying and death quality. Data were grouped for family carer assessments of CAD-EOLD (Comfort Assessment in Dying at the End of Life in Dementia), SM-EOLD (Symptom Management at the End of Life in Dementia) [7, 24], and QODD (Quality of Dying and Death) [42, 43]. Internal consistency outcomes were conflicting (CAD-EOLD and SM-EOLD [7, 24]) or unknown (QODD [42, 43]). CAD-EOLD Cronbach’s α was acceptable (α = 0.74–0.85), but one study [24] lacked adequate sample size (α of 0.72 [[7](#CR7]]; second study’s overall scale α was acceptable (α = 0.78), but subscales were 0.47–0.81 [24]). QODD internal consistency was assessed in one study but rated unknown due to unevaluated factor structure [42]. Content validity for family carer CAD-EOLD and SM-EOLD [24] was unknown due to poor evidence level. QODD had strong structural validity evidence from two samples in one study [43], but variance explained by factorial models was unreported, thus rated indeterminate. CAD-EOLD and SM-EOLD [7, 24] structural validity data were conflicting. Hypothesis testing for CAD-EOLD and SM-EOLD [7, 24] was indeterminate due to lacking hypotheses. QODD showed positive hypothesis testing properties with specific hypotheses and ≥ 75% results aligned [42].

For ungrouped death care tools, most psychometric assessments were unknown or indeterminate. Dutch HCP CAD-EOLD [39] had negative internal consistency (α for subscales 0.64–0.89). German QODD versions for family carers and HCPs (QODD-D-Ang [QODD-Deutsch-Angehörige] [44] and QODD-D-MA [QODD-Deutsch-Mitarbeiter] [45], respectively) had negative structural validity as factor analysis showed factors explained < 50% variance. Cross-cultural validity was assessed for QODD-D-Ang [44], QODD-ESP (Spanish version) [46], and QODD-D-MA [45]. QODD-D-Ang [44] and QODD-D-MA [45] were rated excellent on most criteria, but confirmatory factor analysis was not performed. QODD-ESP [46] had confirmatory factor analysis, but rated limited due to fair scores on criteria: translator expertise, independent translators, and limited forward/backward translation rounds.

Using the ad hoc scoring system, only SPELE (Staff Perception of End of Life Experience) for HCPs [47] and QODD for family carers [42, 43] had positive scores, with moderate-to-limited evidence. Dutch HCP CAD-EOLD [39], family carer QODD-D-Ang [44], and HCP QODD-D-MA [45] were rated negatively.

Psychometric Properties of Tools Assessing Both Quality of Care at the End of Life and Quality of Dying and Death

Table 2 lists death care tools assessing both end-of-life care quality and dying/death quality. Data grouping was not possible due to study differences. Internal consistency was positive for QOD-LTC-C (Quality Of Dying in Long-Term Care of Cognitively intact decedents) [48] (family carers and HCPs) and Korean GDI (Good Death Inventory) [49] (family carers) (α = 0.85 and 0.93, respectively). QOD-LTC (Quality Of Dying in Long-Term Care) (family carers and HCPs [48]) and Dutch HCP version [39] had negative internal consistency. Subscale Cronbach’s α ranged 0.49–0.66 and 0.37–0.75, respectively. Inter-rater reliability was negative for QOD-Hospice (Quality Of Dying-Hospice scale) [50] and QOD-LTC (family carers and HCPs [48]). Japanese GDI (family carers [51]) had negative test–retest reliability (ICC values 0.49, 0.35, 0.52). Structural validity assessments were unknown or indeterminate, except for QOD-LTC (family carers and HCPs [48]) which was negative (model explained 49% variance). QOD-Hospice hypothesis testing was negative despite formulated hypotheses [50] because results did not align with ≥ 75% hypotheses. Cross-cultural validity was unknown for Dutch QOD-LTC (family carers and HCPs [39]) and limited for Korean GDI [49]. GDI [49] was rated limited due to unreported translator expertise and unclear translator independence.

Using the ad hoc scoring system, two of ten death care tools (QOD-LTC-C for family carers/HCPs [48] and Korean GDI for family carers [49]) were rated positively with strong evidence. Four tools (Dutch HCP QOD-LTC [39], family carer QOD-Hospice [50], Japanese family carer GDI [51], and QOD-LTC for family carers/HCPs [48]) were rated negatively; QOD-LTC for family carers/HCPs [48] scored − 8.

Discussion

Findings

This is the first systematic review to appraise psychometric properties and associated evidence levels for post-mortem death care tools assessing end-of-life care quality and dying/death quality. The review identified 33 studies reporting on 35 tools for end-of-life care quality, 22 for dying/death quality, and ten for both. Data grouping was limited by study variability in tool versions, methods, and settings. No single tool was consistently adequate across all psychometric properties.

Half of the tools for care quality were rated positively using our scoring system. CODE [31], despite limited psychometric evaluation post-development, initially showed strong evidence of positive properties across five assessed properties. CODE, a 30-item self-report tool from ECHO-D [27, 28], assesses care setting environment, HCP communication, and patient care in the last days of life. Despite limited use, CODE shows promise and warrants further development and validation as a death care tool. SWC-EOLD [7, 24], predominantly used in long-term care for dementia patients in their last 90 days, also demonstrated strong positive psychometric properties, including internal consistency. This 10-item self-report tool assesses decision-making, HCP communication, dementia understanding, and nursing care. Despite extensive research use, SWC-EOLC would benefit from further psychometric evaluation, especially structural validity and hypothesis testing.

Conversely, Korean CES [40] and CEQUEL [41] showed strong negative and indeterminate ratings, suggesting poor psychometric properties requiring further development and validation as reliable death care tools. Most psychometric properties of dying/death quality tools were rated unknown or conflicting, hindering firm conclusions. For example, cross-cultural validity studies often inadequately described translator expertise and independence.

SPELE [47], a newly developed 63-item HCP tool assessing dying/death quality aspects (environment, symptoms, decision-making, communication in the last week of life), showed moderate positive psychometric properties for structural and content validity. This tool, usable across settings, is promising for further development as a death care tool. QODD [42, 43], adapted and widely used, also has positive psychometric qualities. This 31-item tool measures preparation for death, moment of death, and treatment preferences. Reviewed studies show QODD translated into German and Spanish and used by family carers and HCPs, but it needs further validation, especially for internal consistency and reliability.

Of the ten tools assessing both care and dying/death quality, only QOD-LTC for cognitively intact samples [48] and Korean GDI [49] showed positive psychometric properties. Overall, despite numerous available death care tools, none have undergone full psychometric evaluation across all properties. Further psychometric evaluation of identified tools is needed.

Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review is methodologically strong according to Terwee et al. [52]. It used a broad search strategy without date limits, capturing articles from key databases and reference lists. Measurement property search terms were avoided due to terminology variations, as recommended by COSMIN developers [52]. Some relevant studies were found via reference lists, highlighting indexing limitations. One reviewer (NK) assessed all searches, with three secondary reviewers independently assessing a random sample of 750 titles/abstracts, resolving discrepancies through discussion.

Only studies developing/validating post-mortem end-of-life care and dying/death quality tools were included, excluding studies with secondary psychometric assessments. Studies reporting psychometric properties of translated tools were included to identify cross-cultural evidence, thus not restricting to English tools or populations.

COSMIN provided a rigorous psychometric evaluation framework. However, COSMIN is not designed for studies using methodologies other than classical test theory or IRT, such as generalizability theory. COSMIN items can be subjective, addressed by dual independent assessments and reviewer training for consistency. All assessments were discussed, with a third reviewer for unresolved disagreements.

An ad hoc scoring system was developed for overall tool comparison, providing a qualitative evaluation of psychometric properties. This allows broad scale evaluations, but readers should consider specific scale merits/drawbacks beyond the global score to determine best fit for their study or practice when selecting death care tools.

Finally, this review focused on retrospective quality of care and dying/death assessments, based on proxy ratings by family carers and HCPs post-mortem. Thus, the psychometric evaluations are limited to post-death tool completion and not applicable to pre-death assessments.

Implications

Well-developed and validated death care tools are crucial for several reasons. “Gold standard” tools would enable cross-study and cross-cultural comparisons, improving understanding of similarities and differences across care settings. A global measure would standardize benchmarks for “good” or “bad” deaths, replacing diverse benchmarks like preferred place of death [53]. Some identified tools are population-specific (e.g., dementia [24, limiting transferability. Tools are essential for evaluating interventions aimed at improving care and dying/death quality. Poorly validated tools can compromise intervention result interpretation. This review highlights that, despite numerous available tools, more validation and psychometric property improvement are needed. Researchers and clinicians can use this review to guide tool selection for their purposes, comparing similar tools.

Conclusion

This systematic review critically appraised post-mortem death care tools assessing end-of-life care quality and dying/death quality. It demonstrates a limited number of tools with promising but needing further investigation psychometric properties. Despite many available tools, understanding their psychometric properties is incomplete. Future research should prioritize improving and validating existing tools rather than developing new ones to enhance the field of death and dying assessment.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

PRISMA checklist (DOC 62 kb) (62.5KB, doc)

40271_2018_328_MOESM2_ESM.docx (33KB, docx) Study characteristics of all included studies (DOCX 32 kb)

40271_2018_328_MOESM3_ESM.docx (36.6KB, docx) Characteristics of all tools under review (DOCX 36 kb)

40271_2018_328_MOESM4_ESM.docx (36.9KB, docx) Psychometric and COSMIN evaluation of all individual tools per included study (DOCX 36 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sarah Davis and Jane Harrington and other members of the I-CAN-CARE team, past and present, for their support in completing this research. The authors would like to thank Drs Catriona Mayland and Marco Maltoni for responding to requests for additional information on their studies.

Funding

The improving care, assessment, communication and training at the end-of-life (I-CAN-CARE) programme is funded by Marie Curie (grant reference: MCCC-FPO-16-U).

Author Contributions

PS and ELS conceived the research, obtained funding for the I-CAN-CARE programme, and managed all elements of the work. PS, NK, BC, and BV contributed to the design of the study. NK and BC developed the search terms. NK completed the database searches, reviewed all titles, abstracts, and full-text studies, extracted data from all studies, managed secondary data extractors, and synthesised the data. TA, Jane Harrington, and BV each screened a proportion of the titles and abstracts. BC and TA oversaw the full-text review of studies and data extraction. TA oversaw the quality appraisal and data synthesis. TA, GT-R, GS, NW, SH, and TF completed secondary data extraction and quality appraisal tasks. NK drafted the manuscript, and all authors provided critical review on the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

Nuriye Kupeli, Bridget Candy, Gabrielle Tamura-Rose, Guy Schofield, Natalie Webber, Stephanie E Hicks, Theodore Floyd, Bella Vivat, Elizabeth L Sampson, Patrick Stone and Trefor Aspden have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its ESM files).

Footnotes

The protocol of this systematic review has been registered on PROSPERO, which can be accessed here: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42016047296 (Registration number: CRD42016047296).

References

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA checklist (DOC 62 kb) (62.5KB, doc)

40271_2018_328_MOESM2_ESM.docx (33KB, docx) Study characteristics of all included studies (DOCX 32 kb)

40271_2018_328_MOESM3_ESM.docx (36.6KB, docx) Characteristics of all tools under review (DOCX 36 kb)

40271_2018_328_MOESM4_ESM.docx (36.9KB, docx) Psychometric and COSMIN evaluation of all individual tools per included study (DOCX 36 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its ESM files).